It’s a good thing Dr. Fine’s reputation preceded him, or I might not have stayed long enough to meet him. But first, a segue into the genesis of my ire.

When Corporate America took over health care administration, it decided physicians had wasted too much time taking care of patients instead of generating revenue. Large health care organizations began buying up individual physician practices and, in some cases, taking over hospitals. Younger physicians loved this idea: they got a salary, paid vacation and none of the administrative hassles of running a private practice. (I plead guilty, as I joined an HMO for those reasons. I was a poor businessman and I admitted it. The problem was, in many cases, I knew more about business principles than the people signing my paychecks.)

Older physicians balked at being controlled and some of them resisted as long as they could. If you didn’t play ball, The Corporation would find ways to shut you out. If you didn’t contract with the predominant insurers, you became “out of network” and a lot more costly to patients. Other older physicians saw the handwriting on the wall and retired early, the lucky bastards, to stay at home, engage in hobbies, travel or annoy the wife full-time.

We traded autonomy for financial security and ended up with neither.

The Corporation now controlled everything, including your ass, so it could dictate how you did your job. One physician I knew 25 years ago, a hospital employee, said, “I have guys in three-piece suits telling me what to do. And I do it.” Thus, the standard 10-minute appointment was created. No matter how complex the patient, physicians were expected interview, examine, diagnose and treat a patient in the allotted time before moving onto the next one. Or should I say “mooving on”, since patients were now herded through like cattle. (I often threatened to play the Rawhide theme in the hallway during my HMO days. “Head ‘em up! Move ‘em out!”)

If you were a specialist, you got 20 or 30 minutes for consults, even if the patient had cancer. No “wasting time,” like my gyn oncology professor during residency, who spent an hour discussing ovarian, uterine or cervical cancer with women who were still in shock from the diagnosis.

And now, back to our regularly scheduled blog post.

Dr. Fine’s office booked a 30-minute visit at 2:50 p.m. Peg and I arrived about 15 minutes early; she was still in a wheelchair after having foot surgery. I checked in, sat down and waited. And waited. And waited.

About 40 minutes later a nurse, nursing assistant or whatever, appeared in the door to the inner sanctum and bellowed, “David.” I got up and wheeled Peg through the open door.

Halfway down the hall, the nurse said, “David, what is your date of birth.”

I told her and she said, “Oh, wrong David.” So, I wheeled Peg back to the waiting room while the correct David was whisked away.

Twenty minutes later she reappeared. “David.” Once again, I wheeled Peg down the hallway, but not as far this time before she realized my date of birth didn’t match what was on her tablet. And, once again, I wheeled a now pissed-off Peg back to the waiting room.

Different women appeared at the magic door, calling names as if they worked in a cheap restaurant, and patients disappeared.

It was now 4:15 pm. I’m normally a quiet, patient type (you shaddap and stop laughing!), but even my patience was wearing thin. The first woman we saw opened the door and called, “David.”

“Which one?”

“Last name Rivera?”

“Yeah, that’s me.”

We were herded into a pen patient room and a few minutes later a very sweet assistant came in to verify my information on the computer terminal (paper charts have all but disappeared). She apologized for the wait and said Dr. Fine would see us soon, but he was running behind.

Peg smiled but said, “We’ve been waiting a long time. Dr. Fine better be a rock star!”

The SYT swallowed and assured us Dr. Fine was indeed was, figuratively speaking, on par with Jimmy Page.

We could hear snippets of Dr. Fine’s conversation with another patient. Another 15 minutes elapsed, then yet another nurse/assistant came in with two books. I don’t recall the titles, but they could be titled, “You and Your Prostate,” and “What You Need to Know about Prostate Cancer.”

“The doctor will be in shortly to discuss your diagnosis.”

Now I was pissed! “I’m a physician! I KNOW my diagnosis; Dr. Ky and I have talked about it and I’m here to talk about getting a surgery date scheduled!” I thought If you’d looked at the record before barging in here, you’d know what’s happened and why I’m here.”

Finally, Dr. Fine entered the room and I understood why he was running late. He greeted us and apologized for running late. “Discussing a new diagnosis of cancer with a patient takes some time and I don’t want them to feel rushed.”

Ok, you earned your rock star status.

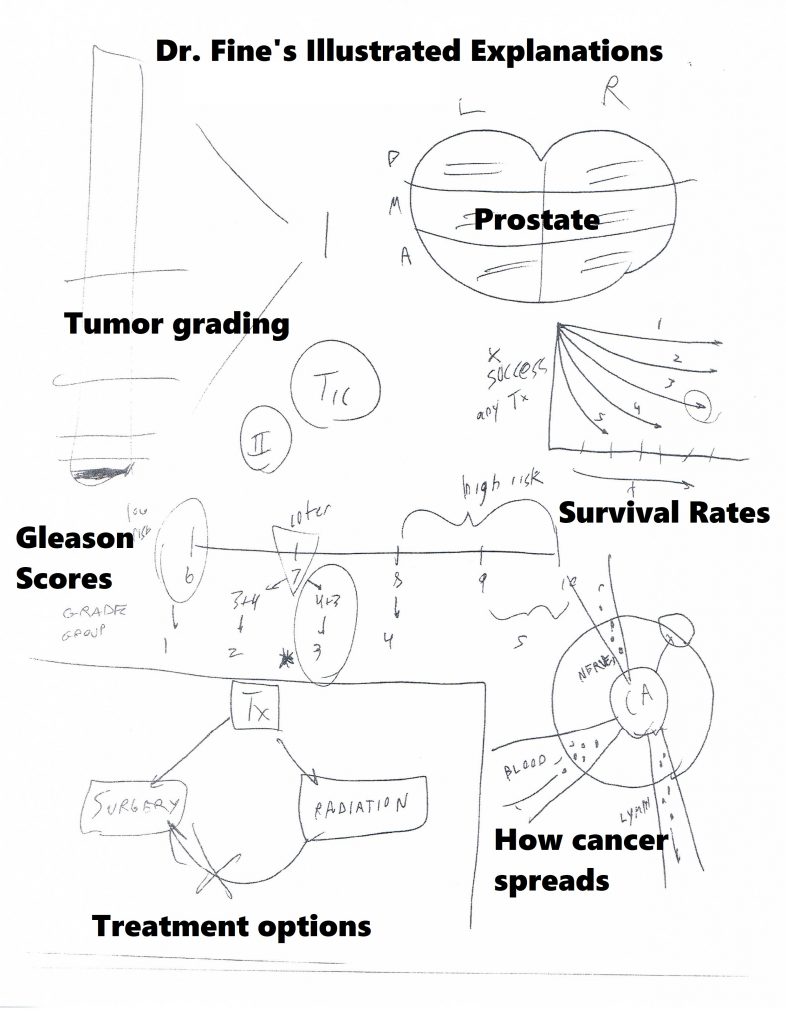

He talked at length about Gleason scoring in general. A Gleason score of 6 suggests one’s cancer is likely to grow slowly while a score of 8 and above is likely to be more aggressive and spread quickly. My score of 7 (4+3) put me at intermediate risk and was more concerning than a score of 3+4. Then he talked about Tumor, Node and Metastasis (TNM) staging and how that relates to overall survival; my cancer stage was T-IIa, meaning no metastases or node involvement. (For more information, go to the Urology Care Foundation educational materials page and download the Localized Prostate Cancer guide.)

We then discussed treatment approaches. I talked about the risks of radiation in my previous post, but the biggest drawback is it turns the prostate to mush. If the cancer recurs, taking out the prostate is next to impossible. Doing surgery first leaves radiation as an option for recurrence.

Surgery removes the prostate completely and, potentially, all of the cancer, but has its own set of risks. Immediate problems include recovering from surgery, including having a catheter in one’s bladder for a week. The surgeon has to cut the urethra (that tube from the bladder to the outside) to remove the prostate, and then sew it back together. One is likely experience some degree of urinary incontinence once the catheter comes out; they recommended getting a large supply of “adult incontinence underwear” along with pads that look like what women wear after delivering a baby.

Surgery removes the seminal vesicles and potentially some nerves along with the prostate, guaranteeing temporary or permanent erectile dysfunction. I would be taking a low dose of the “little blue pill” (sildenafil) every day to “promote blood flow” back into a limp penis. I’d have a checkup six weeks after surgery and then go to the Austin Powers Swedish Penis Enlarger clinic to learn how to use a $300 “medical grade” acrylic cylinder and vacuum pump. For some reason they discourage procuring the much cheaper products available at your friendly neighborhood adult toy store as it could “result in injury.” (Like Ralphie getting his tongue stuck to the frozen flagpole in “A Christmas Story?”)

We agreed to a surgery date right after Thanksgiving. He gave me a card for the Patient Navigator, someone who is supposed to “guide you through the process.” I talked with her once; she told me someone from the hospital “will call you with a surgery date within a couple of weeks. Then someone will call you a week before surgery with questions and instructions.” I used to impart that information to my patients at the end of our visit and didn’t need someone to do it for me.

I saw one of the Urology Department P.A.s (physician assistant) to teach me Kegel exercises, which help control the inevitable leaking bladder after surgery. Women learn Kegels when they are far younger, since they have only one urethral sphincter to men’s three. I told her I’d been wearing protection for months to which she replied, “Welcome to our world.” The visit lasted only a few minutes. Peg had taught me abdominal core and Kegel exercises to do while driving to client’s houses. She did a better job and for free.

About a week later someone from the hospital’s scheduling department called me while I was driving to a client’s house. My surgery would be on December 2 at 7:30 a.m., a wretched time, as I’d have to be there about 2 hours earlier for preparation (which often takes about 30 minutes).

“I’m wandering around the Chicago suburbs so now isn’t a great time to talk. How about you give me a call next Monday when I’m home?”

“Ok, that would be fine. In the meantime, I’ll send you preoperative instructions through our website and we can go over them next week.”

She called and went over my medical history – current and past illnesses; the medications I took; allergies to medications – before going over the same instructions she’d sent the week before. I realize it may seem redundant, but there are people handicapped by a Y chromosome who don’t read or listen and need all the reinforcement they can get.

“Back in the good old days, I used to do all this myself.”

She replied, “You probably weren’t that busy back then.”

Bullshit. I routinely saw 25-30 patients a day in the office and worked in women with acute problems. I did my own preop H&Ps (history and physical) and dictated it on the hospital’s transcription line. Years later, wrote my reports in MS Word and hand delivered them to avoid hearing, “We can’t find your H&P. Did you forget to dictate it?”

Preparing for surgery

Physicians go through “informed consent” with a patient before surgery or a significant treatment. Ideally, a physician explains what s/he proposes doing, what it is meant to accomplish, the risks and benefits of the procedure (including risk of death, if appropriate), and what might happen if the patient refuses. Then the physician gives the patient time to ask questions, have those questioned answered and, often at the end, sign a permit for said treatment or surgery.

This ritual is supposed to ensure the patient makes a well-informed, intelligent decision while also minimizing the risk of litigation in the event of an adverse occurrence or outcome. In reality, a pissed-off patient can always claim “I didn’t know what I was agreeing to” and some lawyer will take the case. So, many of us believe there is no such thing as truly “informed consent.”

My approach to informed consent for surgery went something like this:

“You need to be at the hospital two hours before your surgery time. They will get you ready for surgery (but it doesn’t take two hours, so you’ll spend a lot of time picking your butt). When everyone is ready, one of the nurses will take you to the operating room, put you on the table, hook up EKG leads and strap you down, so you don’t roll off. (Sometimes we will pick our butts waiting for anesthesia to stroll in.) I will be there before you go to sleep. This procedure is going to take about x hours. You’ll go to the recovery room for about an hour and then sent to your room (inpatient) or sent home (outpatient).

“All surgery comes with some risks: risk of bleeding, infection and injury to something inside. You also have a 1 in 60,000 risk of dying from anesthesia, but you are much more likely to die driving your car, especially in the winter when there are a lot of idiot drivers around.” (For the curious among you, the risk of death from a motor vehicle accident is 1 in 103. I can’t find the odds of dying from stupidity, but the Darwin Award people keep a nice tally.)

If I was tying a woman’s tubes (tubal ligation), I added this:

“You also need to understand nothing is perfect, including tubal ligations. About three out of every 1000 women getting their tubes tied get pregnant, sometimes many years later. A few of those pregnancies will end up in the uterus, but many get stuck in the tube, causing an ectopic pregnancy which can kill you if not treated. So, if you ever think you are pregnant, you need to see a physician right away.” (I met a woman in Tennessee who had an ectopic pregnancy 13 years after her tubal ligation. She had been bleeding vaginally (and internally) for a few days, not realizing she was pregnant. I found 1300cc of blood in her abdomen.)

Now, that approach was too vague and informal for Ms. “Expectation Management” who thought researching every possible surgical complication was a fine idea, and then expected ME to grill my surgeon on how the team was prepared to avoid them.

- Ocular edema – high pressure within the eyeballs from prolonged time in the Trendelenburg position, causing temporary or permanent blindness

- Corneal abrasion – scratches in the cornea more often due to dust, sand, poorly fitting contact lenses or catfights

- Brachial plexus injury – upper arm nerve damage making my arms useless

- Compartment syndrome – excess pressure in leg muscle spaces from being in stirrups for a long time, muscle damage from which may necessitate amputation

- Pelvic lymphocele – collections of fluid in the pelvic cavity from removing lymph nodes, or hydrocele – collection of fluid in the scrotum causing it to swell to the size of a cantaloupe

- Atelectasis – collapsed lung tissue from not breathing deeply enough, leading to pneumonia or respiratory failure requiring ventilator support

- Deep vein thromboembolism (DVT) – a clot in the deep leg veins which can potentially break off and travel through the heart and into the lungs, causing instant death from a saddle embolus

I know a lot of the possible complications, which is why I hated gyn surgery! I’m more like Peg’s sister, Michele: Ignorance is bliss.

The day before surgery I had to drink only clear liquids and do a bowel prep. I drank a bottle of magnesium citrate, which is far easier to take than the gallon of NuLYTELY® I had for my colonoscopy prep. But, because a bowel prep can screw up one’s electrolytes, they told me to drink a 20oz bottle of Gatorade four hours before surgery. Yep, 3:30 a.m. Sleep is overrated.

We arrived at the hospital parking lot about 5:30 a.m. and trekked what seemed like a couple of miles to Surgical Registration. I checked in with a woman who was too alert for such an abysmal time. We waited for about 20 minutes, then someone led us on another trek to Pre-Op where I changed into a hospital gown and hopped onto the gurney.

My nurse was an adorable, diminutive redhead with freckles and a pixie cut, too alert and too cheery. She put EKG leads on my chest, a blood pressure cuff on my arm, and poked my finger to check my blood sugar, and started an IV, all while telling me what I needed to do.

“You remind me of my wife.”

“Hey, you brought her here, I didn’t.”

I started laughing so hard she had to retake my blood pressure after I calmed down.

I talked with Dr. Pierce, the anesthesiologist, and reminded him of my paradoxical reaction to Versed (midazolam), a drug used for anesthesia induction and conscious sedation. Dr. Fine appeared a little after 7:00 am for some last-minute discussion and reminders. Surgery would take about two or three hours and I would go home in the afternoon if everything went well. Then the OR nurse put a bonnet on me, had me kiss Peg and rolled me down to the room. I slid onto the table while the anesthesiologist and the scrub tech introduced themselves and got me ready.

The last thing I remember hearing was, “This might sting a little as it goes into your vein.” Click here if you want to see Robotic Assisted Laparoscopic Radical Prostatectomy .

When I woke up 3½ hours later, it seemed as if only ten minutes had passed. I felt pretty good in large part to the local anesthetic injected around the trocar sites. Even the catheter wasn’t uncomfortable. I had something to drink and the recovery room nurse had me walk down the hall. I was home by 3:00 and really happy I didn’t have to stay in the hospital.

The following week wasn’t bad, either. I didn’t have to get up at night because of the catheter. Peg got up at 1 a.m. that first night to empty the bag, but I cut my liquid intake in the evening and emptied it about 11 p.m. which got me through the night. I had six stab wounds for the trocars but only one hurt if I coughed or move wrong, and that only lasted a week. I took three hydrocodone tablets, mostly at night, and used acetaminophen the rest of the time.

The pathology report came back by the end of the week:

Surgical pathology report

Prostatectomy Pathology Report.

A. Right neurovascular bundle margin, excision:

-Neurovascular tissue, negative for malignancy.

B. Prostate, radical prostatectomy:

-Prostatic adenocarcinoma, Gleason score 4+5 = 9.

-The margins of excision are negative for tumor.

-Focal extraprostatic extension, left posterolateral, for a total span of 5 mm.

-Uninvolved seminal vesicles.

C. Bilateral pelvic lymph nodes, excision:

-Six lymph nodes, negative for tumor (0/6).

D. Posterior bladder neck, excision:

-Fibromuscular tissue, negative for tumor.

E. Anterior bladder neck, excision:

-Fibromuscular tissue and focal urothelium, negative for tumor.

So, the cancer cells were worse than the biopsy and it had already peeked out beyond the prostate. Having negative margins means the bad stuff was confined to what was taken out. Surgery turned out to be the more prudent approach.

The catheter came out the following Monday. I had to change underwear frequently for a few days but was back to my pre-surgical level of incontinence by the end of the week. It felt strange being able to urinate like I did before my prostate started squeezing my urethra.

I had an appointment for the Vacuum Erection Device Clinic in January, but that is a whole ‘nother story.