July 20, 1969. I was two months shy of my fifteenth birthday and the warm afternoon sun was coming through the dining room window as I set the table for Sunday dinner in a house that no longer exists. The television had been on most of the day as the world and I waited for Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin to land on the moon.

Almost seven years previously, John F. Kennedy had urged the United States to commit to sending astronauts to the moon and back. “We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things,not because they are easy, but because they are hard…” The Soviet Union had launched the first satellite, Sputnik 1, in 1957 and the first man into space just four years later. At the time most of us did not realize Kennedy’s lofty goal was less about establishing a long-term presence in space but more about beating our mortal enemy, those godless Commies.

Back then we saw science and technology as tools for creating a much better world. Education and knowledge were respected, not dismissed as a liberal conspiracy to undermine our sacred way of life. So, the country rallied around the President and the space program. It seemed our civic duty to follow each mission from launch to splashdown. The three (and only) major networks provided nonstop television coverage of each mission. Some schools brought TV sets into classrooms.

On February 2, 1962 John Glenn became the first American to orbit the earth in his Mercury capsule, Friendship 7. Alan Shepard’s and Gus Grissom’s fifteen minute suborbital flights seemed less important; Glenn became a national hero and the one we all remembered. Kennedy’s issued his famous challenge on September 12, 1962.

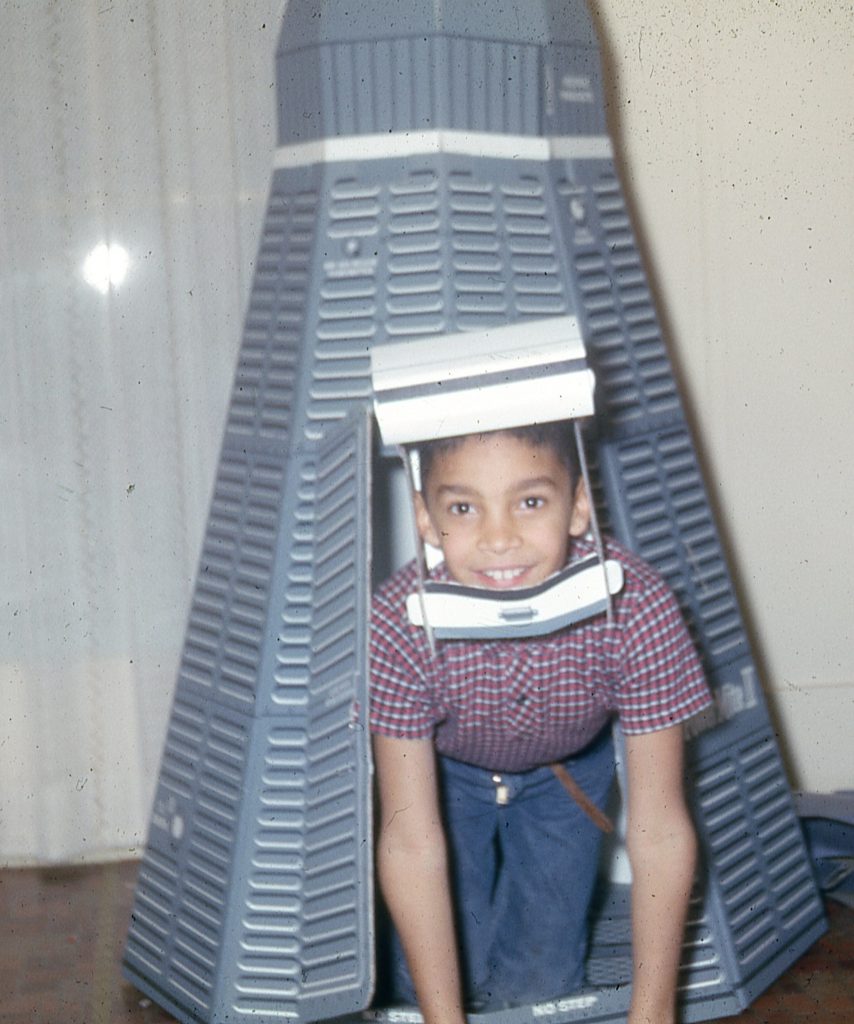

In January 1963, my grandparents sent me a cardboard Mercury capsule, complete with a helmet and a battery operated control panel with blinking lights and dials that whizzed around for a few days before breaking down. Still, it was thrilling to pretend I was an astronaut.

The Gemini program’s first manned launch was in March 1965 almost two years after the last Mercury mission. I watched Frank McGee and David Brinkley, their calm, comforting voices, covering the Gemini missions for NBC, “sponsored by Gulf Oil Corporation.” (Click here for the NBC Special Reports open and close, which preceded any major announcement, from space shots to LBJ’s health status.) Brinkley’s droll delivery reminds me of Obama, especially in this clip, (at 1:30), when he remarks, “It seems to me, um, the age of the computer had to arrive before the age of space, didn’t it?” (I’ve found the networks’ breathless coverage of the 50th anniversary rather irritating.)

Among my few memories of Gemini are building Revell’s plastic model and watching SPECTRE’s bad guys capture a Gemini capsule in orbit at the beginning of the fifth Bond film, You Only Live Twice. Ed White stepped outside of Gemini 4 on June 3, 1965, becoming the first astronaut to walk in space, another milestone. But I think interest started to dwindle over the next year, as we became concerned with the turmoil on earth. The war in Vietnam was ramping up. Newark, Detroit, Minneapolis and other cities would explode in rage and fire in July 1967. The world I’d known was disappearing. Or maybe it had always been this way and I’d been oblivious.

On January 27, 1967 astronauts Gus Grissom, Ed White and Roger Chaffee died gruesome deaths after a spark from faulty wiring ignited the pure oxygen environment in the Apollo 1 command module during pre-flight testing. We heard about it the next evening when Jules Bergman, ABC News’ Science Editor, somberly read a script from the ABC News desk. There were no 24-hour news channels back then; no instantaneous and continuous coverage. It happened, it was over, and we went back to our lives. (Nineteen years and a day later the space shuttle Challenger exploding 73 seconds after liftoff; we watched the disaster on an endless loop.)

I didn’t follow any of the Apollo missions during the next two and a half years, having descended into the depths of teenaged angst and cynicism. Apollo 8’s Christmas Eve broadcast from lunar orbit seemed quaint and hollow after I’d watched Chicago cops beating protestors and CBS news teams during the 1968 Democratic Convention.

But then came Apollo 11 and the moon landing.

Apollo 11 launched on July 16, 1969 and, after making one and a half trips around the earth, the third stage ignited, sending the modules and the astronauts towards the moon. The CSM separated from the third stage, turned around and extracted the LM. All this happened within a few hours. Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin entered the LM on July 18 for preliminary checks during the three-day trip to the moon; the craft entered into lunar orbit on July 19. (Vox has an excellent summary of the mission here.)

And we waited.

On July 20, 1969 the LM Eagle undocked and separated from the CSM Columbia at 12:44pm CDT. The two would stay in orbit together until Eagle entered its descent orbit at 2:08pm CDT. The descent engine fired at 3:05pm CDT and Eagle began the nail-biting final trip down to the moon’s surface. Hundreds of millions of us were now glued to their television screens. (You can watch a long version, 19m 52s, of the final approach here. If you want the Cliff Notes version, 4m 30s, click here.)

I remember watching the black and white pictures on our console TV. As Eagle neared the surface a long probe, looking like a needle about to pierce the skin, appeared at the top of the screen, growing larger until the module’s shadow blotted out most of the view. At 3:17pm, Neil Armstrong uttered the first of two famous phrases, “Houston, Tranquility Base here, the Eagle has landed.”

Neil Armstrong finally stepped onto the moon’s surface six hours later, delivering those unforgettable words: “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” The video quality wasn’t the best, but coming from 250,000 miles, it was awe-inspiring and humbling. The world was one for a brief time.

AFTERWORD

Jethro Tull’s album, Benefit, hit U.S. shelves in May, 1970. I’d been listening to it for forty-some years before actually reading the lyrics to “For Michael Collins, Jeffrey and Me.” The verses rival Steely Dan in ambiguous, but chorus is Michael Collins, the man who stayed in the CSM, telling Armstrong and Aldrin to be careful and lamenting he couldn’t be with them

“…I’m with you L.E.M.

Though it’s a shame that it had to be you

The mother ship

Is just a blip from your trip made for two

I’m with you boys

So please employ just a little extra care

It’s on my mind

I’m left behind when I should have been there

Walking with you…”

So, have a listen before you go.

Apollo image (c) Can Stock Photo / merlin74