January – the month when millions of people engage in that time-honored bald-faced lie known as the New Year’s Resolution. “This year I promise I will exercise more, get in shape and lose weight.” (I resolved to get this posted in January, and you can see how well THAT worked out!) It’s about as successful as when my sister-in-law vows to give up throwing F bombs for Lent. One year she made it to 4:30pm on Ash Wednesday; usually she doesn’t make it out the door. Most people have given up on their resolutions sometime between January 12 in Australia and January 17, known as Ditch New Year’s Resolution Day.

Losing weight is one of the most common New Year’s resolutions but often remains an exercise in futility. The New England Journal of Medicine acknowledged the problem in the January 1, 1998 issue, noting ”the vast amounts of money spent on diet clubs, special foods, and over-the-counter remedies, estimated to be on the order of $30 billion to $50 billion yearly, is wasted.” Twenty-some years later the weight loss industry rakes in over $60 billion a year but only about 5% of dieters manage to keep from regaining weight. Most of the Biggest Loser contestants regain most of their weight over time.

So how did we become so obsessed with weight?

In 1901 Dr. Oscar Rogers, Chief Medical Director of the New York Life Insurance Company, reported that overweight men had a 35% higher death rate. Insurance companies latched onto this finding and assumed the obese presented a higher actuarial risk. Rogers also discovered overly tall and underweight men suffered a higher mortality rate, but conveniently left out those data.

In 1930, Louis Dublin, Metropolitan Life Insurance Company’s vice-president and statistician, linked obesity to long-term illnesses – heart and kidney disease, diabetes, atherosclerosis and stroke – and obesity became permanently stigmatized. The obese stood accused of a variety of psychological disturbances, including depression, gluttony, homosexuality, laziness and anxiety.

Met Life published “ideal” weight and height charts for men and women in 1959 and 1983, but they were based on very sloppy data obtained from white collar people who could afford life insurance policies. Some of the data were self-reported; men over-reported their heights and women under-reported their weights. Dublin’s body frame sizes – “small, medium and large” – were arbitrary. No one considered muscle mass and physical activity; by these measures, many highly trained athletes would be considered overweight.

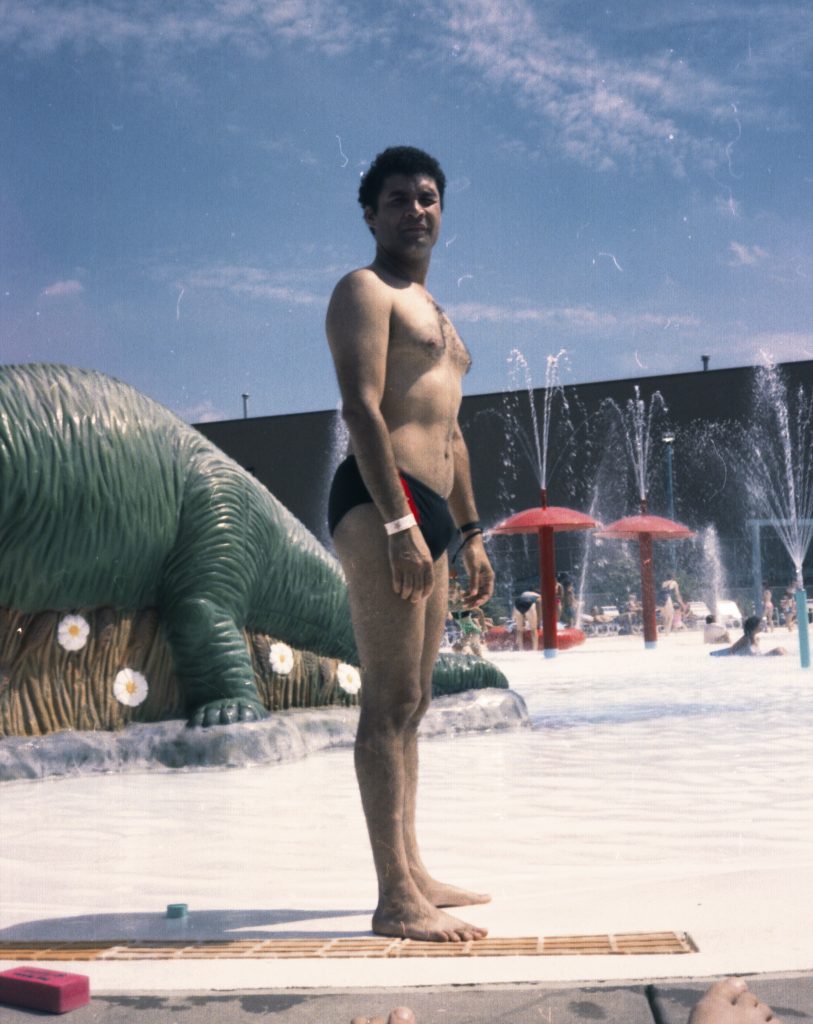

I’m six feet tall with a “large” frame. The Metropolitan Life Weight Chart for Men says my “ideal” weight should be 164-188 pounds. This is what I looked like in 1991: 175 pounds with a 34-inch waist.

I looked pretty good, right? Well, I was in my 30s and had lost 35 pounds because I’d stopped eating for days at a time when I was going through a painful divorce. Over the next few years I gradually gained most of it back, stabilizing at 220 pounds. I gained another 40 pounds from job stress eating in the late 1990s; my weight fluctuated between 260 and 270 pounds for the next fifteen years. A few years ago, I dropped below 250 pounds, but that was the result of two relatively severe respiratory illnesses. I could eat or breathe, but not both.

The hysteria over obesity was compounded in 1993 when two public health researchers, J. Michael McGinnis, MD and William H. Foege, MD, published “Actual Causes of Death in the United States” in The Journal of the American Medical Association, from which the media erroneously concluded “obesity kills 300,000 people each year.” If one bothered to read the article, one found the authors reported “diet and activity patterns,” not obesity, per se, contributed to mortality. The authors cautioned “no attempt was made to further quantify the impact of these factors on morbidity and quality of life,” and the “numbers should be viewed as first approximations.”

McGinnis and Foege compared the National Center for Health Statistics’ (NCHS) list of the most common causes of death – heart disease, cancer, strokes, accidents, diabetes, and others – with factors that contributed to mortality, such as tobacco, alcohol, guns, cars and the aforementioned diet and activity patterns. The NCHS found almost twice as many people died from accidents as from diabetes; however, no one suggested we had a national epidemic of stupidity or clumsiness.

| NCHS Causes of Death | Annual Deaths | McGinnis/Foege Contributors to Mortality | Annual Deaths | |

| Heart disease | 720,000 | Tobacco | 400,000 | |

| Cancer | 505,000 | Diet /activity patterns | 300,000 | |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 144,000 | Alcohol | 100,000 | |

| Accidents | 92,000 | Microbial agents | 90,000 | |

| COPD | 87,000 | Toxic agents | 60,000 | |

| Pneumonia/influenza | 80,000 | Firearms | 35,000 | |

| Diabetes | 48,000 | Sexual behavior | 30,000 | |

| Suicide | 31,000 | Motor vehicles | 25,000 | |

| Liver disease | 26,000 | Illicit drug use | 20,000 | |

| HIV | 25,000 |

ARE THINGS REALLY THAT BAD?

Data from the NCHS and other sources suggest the answer is “no:”

- Deaths from cardiovascular disease have declined since the 1950s.

- Life expectancy in the US, which peaked at 78.5 years in 2012, has dropped three years in a row due to drugs and suicide, not obesity.

- The US Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine compared the fitness level of new recruits in 1978 and 1998 and found the latter were just as fit as the former, albeit 10% heavier.

- The relative risk of mortality associated with obesity declines with age.

- Obesity is associated with a variety of maladies, but a direct cause and effect relationship hasn’t been established. If 30 percent of overweight people are diabetic, that means 70 percent of them aren’t. If 85 percent of diabetics are obese, and Type 2 diabetes is due to insulin resistance, then which came first, the obesity or the diabetes?

- Paradoxically, one research group tracking normal weight and obese patients after being diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes found those of normal weight were more likely to die than their obese counterparts.

So why is it so difficult to lose weight and keep it off?

For decades physicians told us if we all just ate less and got more exercise, we’d all look like Adonis and Aphrodite. If you were fat, it was your own damned fault because you were gluttonous or lazy. Researchers have only recently started admitting that weight gain is far more complicated than “calories in – calories out.” Weight regulation is a complex interaction of genetics, environment and biology, and long-term weight loss is nearly impossible for most of us.

The magnitude of genetics’ role in obesity isn’t entirely clear, but we know susceptibility to “common obesity” involves multiple gene variants, first identified on chromosomes 16 and 18. Studies of familiar relationships found the correlation for BMI in identical twins is twice that of fraternal twins and decreases as genetic separation increases: siblings, parent-child, spouses, and adopted children. Pick your parents carefully if you want to look like a cocaine waif your entire life without the drug risks.

Thousands of years ago, when we chased our dinners across the savannahs (or ran to keep from becoming some critter’s lunch), humans adapted genetically (so-called “thrifty genes”) to hang onto whatever calories they ingested as a hedge against times of famine. Western civilization has brought us a surfeit of food along with soul-sucking jobs that have most of us sitting on our butts for 8-10 hours a day (more if you factor in 2-hour daily commutes in large cities). Our bodies have not adapted to this relatively sudden change.

The Pima Indians of Arizona provide an extreme example of environment rapidly overwhelming centuries of a lifestyle that had kept a genetic propensity for obesity in check. Robert Pool, in his book Fat: Fighting the Obesity Epidemic, described the Pima this way:

“When the white settlers first arrived, they found Indians straight out of a Frederic Remington sculpture. The bodies of the Pimas were thin and sinewy, their legs chiseled by regular running, their arms strong from the bow, the war club and the plow. Today the Pimas are fat. Not just chubby or overweight, like the average American couch potato, but obese.” (Pool, p. 140)

A century and a half after being consigned to a reservation, the Pima have gone from being fierce warriors protecting the weak to a tribe devastated by high rates of diabetes, obesity and kidney disease. Their life expectancies are fifteen to twenty years shorter than the average American. Much of this appears to be the result of a sedentary lifestyle and a diet that has changed from a high-fiber, low-fat, low-calorie diet to one with a lot of empty sugar calories and triple the fat content.

Our own lurch towards diabetes and obesity appears to be linked to the low-fat craze that started in the mid-1970s. “Fat is the enemy!” “Carbs are good for you!” The food industry capitalized on this, producing a large range of low-fat foods, which we all gobbled up – and got fatter. Decades later, we learned the sugar industry started paying off researchers in the 1960s researchers to blame fat for obesity. Ironically, European countries with higher-fat diets had lower incidences of heart disease.

While it’s convenient to blame genetics and environment, biological mechanisms don’t help much. Researchers debate whether there is a single “set point” or multiple “settling points,” but most people who’ve lost weight will tell you how their bodies will fight like hell to get it back. Columbia University’s obesity researcher, Rudy Leibel, compared energy expenditures of twenty-six obese people with static weights, averaging 335 lbs., to those of twenty six normal weight controls. As expected, the obese required more calories than the normal subjects to maintain their weights. (Calories per day/weight (lbs.) = calories per pound)

However, when the obese lost significant weight (about 115 lbs. each), they required FEWER calories than expected to maintain their weights. Their metabolisms slowed in an effort to return to their original weight. Kevin Hall, a researcher at the National Institutes of Health, found the Biggest Loser contestants’ metabolisms remained low even after they started to regain weight.

What should you do?

First, weight alone is a poor indicator of overall health. Jim Fixx, the man who got America running, died of a heart attack in 1984 while jogging in Vermont. Dana Carvey, a perennially skinny guy whose genetically high cholesterol levels (familial hypercholesterolemia), has required four angioplasties to stay alive.

On the other hand, in 2002 the San Francisco Chronicle did a story on Amanda Wylie, a 250-lb. aerobics instructor in San Francisco who had a black belt in boxing, did yoga and the splits, and could probably wipe the floor with me. That same year, Jennifer Portnik, another obese but physically fit aerobics instructor, sued Jazzercise for refusing to sell her a franchise. She opened her own business after being certified by the Aerobics and Fitness Association of America, and Jazzercise dropped its requirement for skinny instructors.

Steven Blair and others at the Cooper Institute for Aerobics Research, found that skinny couch potatoes were at greater risk of dying than men – skinny or obese – who maintained cardiovascular fitness. Exercise isn’t going to make you lose a lot of weight, but it’s great for your heart. So, go take a walk, find a physical activity you like, and minimize couch time.

Recently (February 13, 2019) Samantha Bee took on how media and physicians stigmatize fat people in a Full Frontal segment called “Thicc not Sick.” (I was appalled to find out news outlets refer to stock footage of the obese as “guts and butts”). Twelve years ago, a genetically scrawny medical school classmate badgered her husband into losing weight (I didn’t think he was terribly heavy). I found a Facebook photo from last year. He’s back to his original weight and still looks pretty good.

Realize diets don’t work in the long term because they are merely a temporary change. Anyone can lose weight eating 800 calories per day, but are you willing to do that for the rest of your life? Probably not. Your metabolism will adjust to compensate for the weight loss, rendering permanent weight loss an exercise in futility for most of us.

There is no single, optimum diet for everyone, so find what works. Peg and I have a low-carbohydrate, high-protein diet, but she can eliminate carbs more easily than I can. My blood sugar will plummet in an hour or two if I don’t have a little carb with my meals. (That, and I get really ugly.) The best thing you can do is eat a relatively healthy diet and give yourself rewards in moderation.

Finally, I think the unrelenting stress of our jobs presents the greatest risk to our overall health (Midwestern winters run a close second). Obstetrical nurses often live on chocolate because they don’t have time to eat while working on chronically understaffed units. Corporate America learned how to squeeze more work out of fewer people for less money and they dare not squawk. “If you don’t like it, you’re free to leave and we’ll find someone who is more of a team player.”

Misery loves company. We’re stuck with work but socializing outside of the workplace and fostering supportive relationships will make life a lot easier. And wine. Everything goes better with wine.