Thursday

It started out as a repeat of Wednesday. A lab tech drew blood around 5am which turned out to be yet another set of troponin ($254.00) and lipase ($197.00) levels and a third comprehensive metabolic panel ($202.00) and CBC ($92.00) plus $37 just for the honor of sticking a needle into my veins.

Meghan arrived at 6am to give me my daily Protonix® for reflux; Katrina would bring me the rest of the medications after shift change. This time I balked at the Lovenox.

“Do I really need that? I’ve been out of bed several times and I move around when I’m in bed, so I’m not really going to throw a clot.”

“Ok, well, you don’t have to take it if you don’t want it. I’ll let the doctor know.”

“While you’re at it, how about asking him to get rid of the telemetry monitor since we know I didn’t have a heart attack and this thing is probably costing someone a lot of money.”

Telemetry was $122.00 per hour and the total charge was $2,074.00 with another $2652.00 “room charge” tacked on.

Then the Parade of the Grey Coats started.

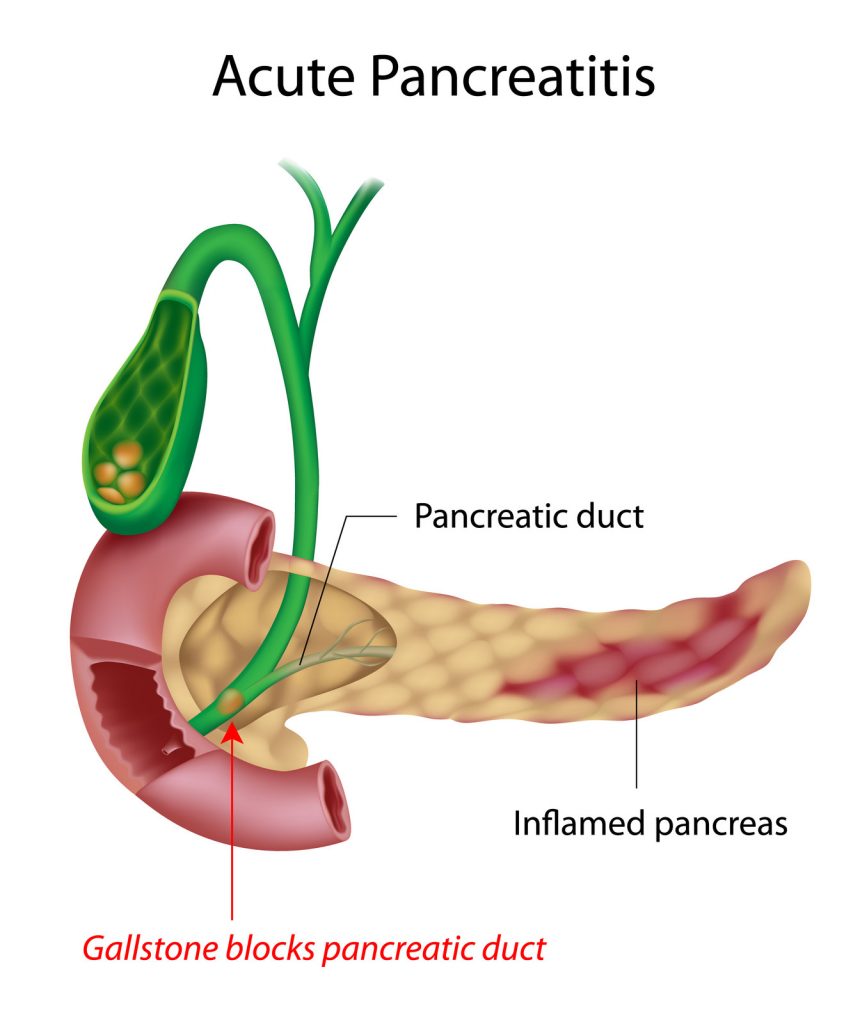

I don’t remember much of what the hospitalist said, aside that my lipase level was back to normal, and he would be talking with the surgeon about our conversation. Peg arrived shortly after he left.

I’m really not sure why the gastroenterologist showed up because he had nothing useful to say. Probably it’s because he could bill $366.30 for the initial consult and $192.03 for the follow up visit. He told me to make a follow-up appointment with him in four weeks, advice I promptly ignored because I’d already made an appointment with my own gastroenterologist to arrange another colonoscopy.

My cardiologist, Dr. McGuinness, recognized me immediately when he arrived. He is also my sister-in-law’s cardiologist, in the same group as her “electrician,” and he is beloved by staff and patients. He should give seminars on bedside manner and patient communication.

“It’s good to see you. I wanted to let you know your stress test was negative. I heard you might be having your gallbladder out soon.”

“Yes, I talked with Dr. DeBouw last night; he should be coming around this morning so we can finalize a plan.”

“There’s nothing more for us to do, so we’re signing off. I hope surgery goes well.”

“Thanks. It was good to see you.”

Peg was in a good mood. However, Katrina, who must have sensed a critically low level of turmoil, arrived to top off the tank.

“Dr. Warner, the hospitalist, said he talked to Dr. DeBouw who said he would talk to you downstairs in pre-op before surgery.”

Peg and I looked at each other.

“Where did you leave it last night?”

“He was going to talk to me this morning about doing surgery now or schedule it for a couple of weeks later as an outpatient.”

“He didn’t say ‘We’re going to take you to surgery tomorrow,’ did he?”

“Nope.”

“Well, I hope he’s better in person because right now I’m not happy.”

If momma ain’t happy, ain’t nobody happy!

This could have been problematic. Insurance companies don’t like to pay inpatient rates for outpatient procedures unless done as an emergency, in which case one has to have been formally admitted. Peg had called the claims department on Wednesday and, as of 3:40pm, they had only received notification of my emergency room visit. They weren’t aware that I’d been held for observation, nor whether I’d been admitted. The person in claims said, “Some hospitals are better than others.”

Peg asked Katrina: “Who can I talk to about this? Utilization management?”

“That would be a good place to start; you can call the operator and they’ll connect you. You can also talk to the unit manager. I think she is on the floor today.”

Hospital Utilization Management (UM) departments are the bane of every physician’s existence. Utilization reviews ostensibly increase efficiency in hospital care and decreases revenue loss from unreimbursed charges by reviewing care for “medical necessity” and decreasing “length of stay.” Physicians see UM as people paid to tell us what we’re doing wrong and why we should toss patients out “quicker and sicker.”

Peg called UM and got voicemail, which didn’t improve her mood. I called Katrina back into the room.

“Would you do a couple of things for me? First, have someone get ahold of Dr. DeBouw and let him know we want to see him here in the room, not in pre-op. I don’t know if there’s been a problem with communication, but I think it’s tacky to assume someone has agreed to surgery without a final discussion. Then can you find the unit manager because trying to talk with someone in Utilization Management was a bust.”

I sensed some annoyance, but she agreed to contact him. A few minutes later she returned and told us he was on his way to the hospital and would see us before his first surgery. I hated to be demanding, but this is why physicians and nurses need to be on the other side of the bed. It gives the perspective one wouldn’t get without being subjected to the indignities inflicted on the great unwashed.

Dr. DeBouw arrived about 30 minutes later. He reiterated what we had talked about the prior evening, including the risks of becoming seriously ill while waiting to do surgery as an outpatient. Peg was happy again.

Someone from patient transportation came to fetch us around 12:30pm and took us to pre-op holding where patients are prepped for surgery. If you’re lucky, you’ll be put into a 10×12 ft. cubicle with a sliding glass door and a privacy curtain. There’s enough room for the gurney, a small wall-mounted desk and cabinet, an I.V. pump and one family member sitting in an uncomfortable plastic chair. The back wall usually has a fluorescent light bar, a wall-mounted monitor screen, and a “medical headwall system” which has outlets for oxygen, “medical air” suction and electricity. Often there’s a self-inflating resuscitation bag and mask hanging on the wall just in case someone codes in the room. Otherwise, you’ll likely be in a ward with several patient areas separated by curtains, which is also how most Post Anesthesia Care Units (PACU) are set up.

A lively nurse peeked around the curtain and said, “Your doctor will come and talk to you before we take you back.”

“Uh, we talked with him upstairs about thirty minutes ago.” Geez, doesn’t ANYONE communicate around here?

“Ok then, that makes it easier. What’s your name and date of birth? And what are you having done?”

If I’d thought more quickly, I might have made some smartass comment about having a Cesarean section for twins, but I was really tired and just wanted to get on with it.

The anesthesiologist followed. Anesthesiologists range from gregarious back-slappers through personable, reassuring people to grumpy assholes who speak in grunts. The stereotype of anesthesiologists are physicians who, much like emergency room physicians, prefer short-term, intense patient relationships, minus the need for engaging or conversing.

“What’s your name and date of birth? And what are you having done?” He wouldn’t be the last person to ask me that.

After identifying my name, my quest and my favorite color, I told him about my paradoxical reaction to Versed (midazolam), a benzodiazepine used for sedation for procedures, such as colonoscopies or minor surgeries that don’t require general anesthesia. I’ve been given it for two colonoscopies and my eyelid surgery; apparently, I tried climbing off the table for the first two and a nurse had to hold my head for the third. I don’t remember any of this because Versed puts one in a little black room without anything to distract, like elevator music.

“They gave me 6mg when I had my eyelid done.” (The usual dose is 2mg.)

“What??? That was wrong! If the usual dose doesn’t work, giving someone more certainly isn’t going to help.”

“Well, they ended up giving me propofol.”

He made a note in my chart and left. A few minutes later the Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetist (CNRA) came into the room. For the uninitiated, a CRNA is a registered nurse who has gone beyond a Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN), earning a Master of Science in Nursing (MSN) and completing two to three years of anesthesia training. They’re often supervised by anesthesiologists in large hospitals, but often practice independently in smaller, rural hospitals. They are cheaper to train than physicians and their salaries, while substantial, are much lower than anesthesiologist salaries.

I like CNRAs because I don’t have to deal with an outsized ego. With few exceptions I’ve found them to be a joy to work with.

Then the moment of truth arrived. I kissed Peg as they wheeled me out the door and down the hallway. Then down another hallway. And another. By now we should have reached the next county. Finally, they pushed the gurney into the room, and I climbed onto the operating table. The anesthesiologist put a mask over my face and told me to breathe deeply.

I heard, “How are you doing?”

“I’m still here.”

Not for long, sweetheart.

I’m thoroughly fascinated by general anesthesia. You’re out like a light and before you know it, you’re in the PACU babbling like an idiot. My prostate surgery took three and a half hours, but it felt like ten minutes to me. This was no different. When I woke up in recovery, I asked myself am I dreaming? I’ve had fairly vivid dreams that are almost indistinguishable from real life until I finally wake up. I asked “am I dreaming” out loud but there was still no answer. Slowly things started to come into focus, and I suspected I wasn’t in the OR.

I saw a recovery room nurse next to the gurney, making notes in the laptop sitting on the bedside table. I put my hand on her shoulder to make sure she was real. She took my hand away and looked at me.

“You’re in recovery. Do you need anything?”

“How about a beer?”

“No, there’s no beer”

“I want a beer.”

“Nope, no beer.” Well, THAT sucks!

I became aware of a rhythmic beeping sound above my head and to the left, the pitch of which began to slowly decline.

“Take a deep breath.”

I did and the pitch rose. I nodded off and the pitch dropped.

“You have to breathe. Take a deep breath”

The beeping sound was coming from the pulse oximeter, a device which measures the percentage of blood oxygenation saturation (also known as O2 sats) through a small sensor clipped to one’s index finger. Anything above 98% in a healthy person is normal. I’ve had lifelong asthma and chronic inflammation, so my sats run around 95% on a good day.

I looked over my shoulder; my O2 sat was 89% and going down. I took a few deep breaths and it rose to 98%. Every time I heard the pitch going down, I looked at the oximeter and adjusted my breathing because I don’t like being yelled at even though I know I’m just fine. I’m not breathing deeply because I just had three tent stakes thrust through my abdominal wall and I was breathing anesthetic gas, which I could still taste an hour later.

“Would you like some ice chips?”

“Yes, please.”

She dumped a spoonful of ice chips into my mouth which I savored, waiting for them to melt instead of chewing.

“Can I have more ice?”

Another spoonful of cool, wet ice chips. I could hear several people at the desk discussing Portillo’s, a well-known Italian beef joint in the area. That sounds good. Portillo’s and a beer.

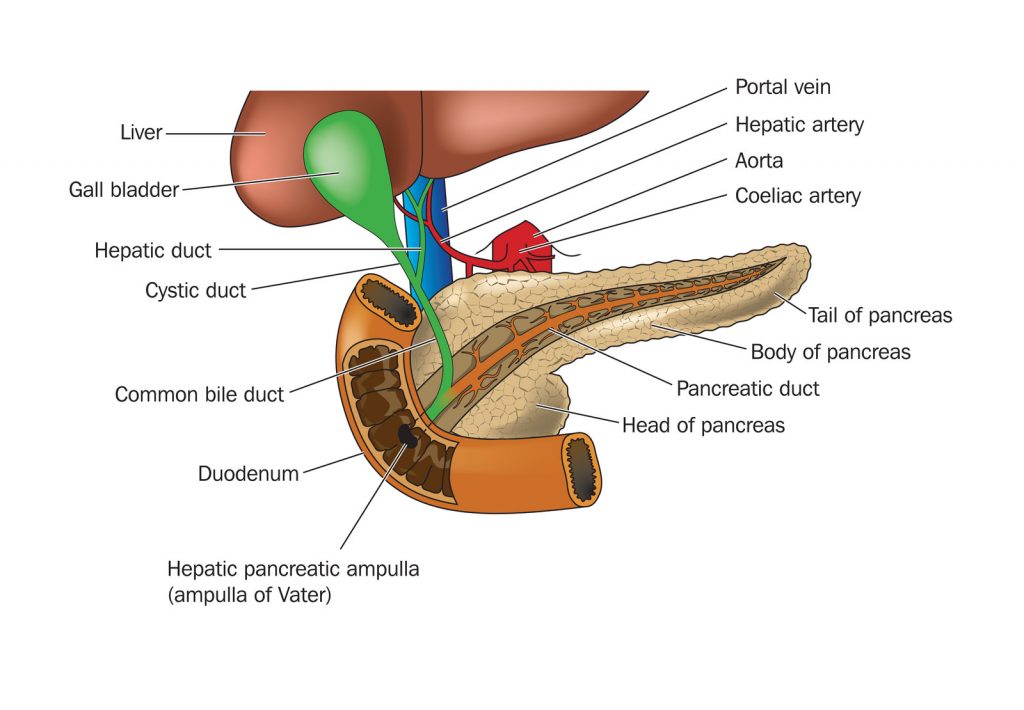

Dr. DeBouw talked with Peg after he’d finished. My gallbladder was “ugly” and there were more stones marching down the cystic duct, so taking it out was prudent. He said surgery was “textbook” and took about 20 minutes. If recovery went well, I could go home later in the afternoon and have anything I wanted for dinner, even steak.

That sounded good, but someone hadn’t bothered to tell PACU or the floor to which I was going to be transferred. Normally, one goes from PACU to another outpatient area where the staff assesses one’s fitness to go home. “What we’ve got here is failure to communicate.”

Patient transportation took me to the fourth floor and dumped me off in a room the size of a storage closet. There was barely enough room on either side of the bed for one person. Someone had dutifully filled out the white board facing the bed with pertinent information like my nurse and her in-house phone number, my physician and what tasks had been scheduled for the next 24 hours. My new young nurse, Ashley, and her equally young assistant bounced into the room, bright-eyed and bushy-tailed, even though their shifts would end in a couple of hours. Ashley immediately hung a fresh I.V. bag (another one hundred fourteen bucks a bag and another $753/hour for the pump).

“Let’s get you settled in…”

“Uh, I’m not planning on staying here for very long. Dr. DeBouw said I could go home this afternoon.”

“Uh… Well, let me check on that. I thought you were going home tomorrow morning.”

“Not if I can help it. I’ve been here long enough.”

She left the room, presumably to call my surgeon and confirm that I was indeed getting out of Dodge and returned in a few minutes.

“Yes, you can go home but before that you have to eat something, urinate and walk without difficulty.”

“Ok, well I peed while you were gone. If you want me to walk, let’s go now!”

“How about I have you order something from the menu, and we can walk while you’re waiting for it.” (Being able to order something charitably called “room service” is a recent development in hospital management. It’s still hospital food and sucks more often than not.)

Surgeons often inject long-acting anesthetic into the tissue around the trocar sites; I wouldn’t feel any pain until the following morning. I got out of the bed with little effort, grabbed the I.V. pole and led my nurse and her assistant out the door. I went down the hall and circled the nursing station at a brisk walk, the two of them marveling behind me as if Christ had just healed the cripple

“Well, just look at you go!”

You’re young and you think I’m ancient, but your perspective of age will change in about forty years. People in their sixties are no longer hanging out on Death’s doorstep. Neither are many people in their eighties.

My “dinner” arrived shortly after we returned to the room: desiccated grilled chicken and that tasteless broth I’d experienced the day before. The only saving grace was a small carton of Luigi’s Lemon Italian Ice. Very tasty.

Ashley bounced into the room again.

“We’re trying to contact the hospitalist because he has to approve your discharge?”

“Why? The surgeon already discharged me. Why would the hospitalist care if I’m gone?”

“Well, we just have to do it, but it shouldn’t be long. He’s already left the hospital but we’ll page him.”

After waiting another 45 minutes for the hospitalist’s blessing and satisfied that I met the criteria that would keep them from being sued for discharging me too early, they gave me the requisite discharge and follow-up information. Patient transportation wheeled me to the main entrance, stopping at the canopied walkway leading to the parking lot pickup point. He must have been tired after a long day.

“Can you make it from here or do you want me to wheel you out?”

“Nope, I’ll take it from here.”

I got into the car and Peg drove off. We stopped by Walgreens and picked up my prescription for hydrocodone tablets (I used only one), then Portillo’s for a beef sandwich before going home to my own bed. But no beer.

Here’s the damage:

| Description | Charges |

| Hospital | $47,914.92 |

| ER Physician | $1,264.00 |

| Medical Group Physicians | $1,850.01 |

| Outside GI Consultant | $558.33 |

| Surgeon | $2,900.00 |

| Surgical Assistant | $1,450.00 |

| Anesthesiologist | $2,475.00 |

| CRNA | $2,475.00 |

| Radiologist | $488.00 |

| Pathologist | $73.00 |

| TOTAL | $61,448.26 |

I have good insurance which paid for most of this. We still had to pay more than $2400 out of pocket, but Peg is fortunate enough to have a Health Savings Account (HSA), which is funded with pre-tax dollars. I reached my deductible before the anesthesia group submitted its bill for both the anesthesiologist and the CRNA, $2475 each. So much for CNRAs being cheaper.

I can afford this but millions more can’t. It’s unconscionable that the richest country in the world won’t provide universal health insurance coverage. I don’t see that happening until Millennials and women run government.

(If you are interested in seeing how a gallbladder is removed laparoscopically, check out this video: Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy for Symptomatic Cholelithiasis – Extended L. Michael Brunt, MD, Section of Minimally Invasive Surgery, Washington University, St. Louis, MO.)

Sad Gallbaldder Plushie from The Awkward Store, courtesy of my wise-ass daughter. Now why didn’t I think of this 20 years ago?