(I took a few months off because I didn’t have much to say. and I wanted the tangible rewards of “döstädning” (Swedish death cleaning). We emptied the storeroom Peg rented for her parents‘ things after her father’s passing. The memorabilia and the coming New Year’s Eve folderal prompted this memorial.)

Many people make resolutions on New Year’s Eve, most of which won’t last the month. But this one lasted a lifetime.

Mike was born in Chicago in 1919 to James and Anna Sullivan, immigrants from Ireland and Yugoslavia, respectively. They lived on the West Side of Chicago where the Irish and Italian neighborhoods met. His father worked for the railroads and his mother was a housewife; back then married women didn’t aspire to anything else. His little brother Johnny was born a few years later. Mike and his family emerged from the Great Depression intact but, like many from that time, he saved every little thing because, “you never know when you might need it.”

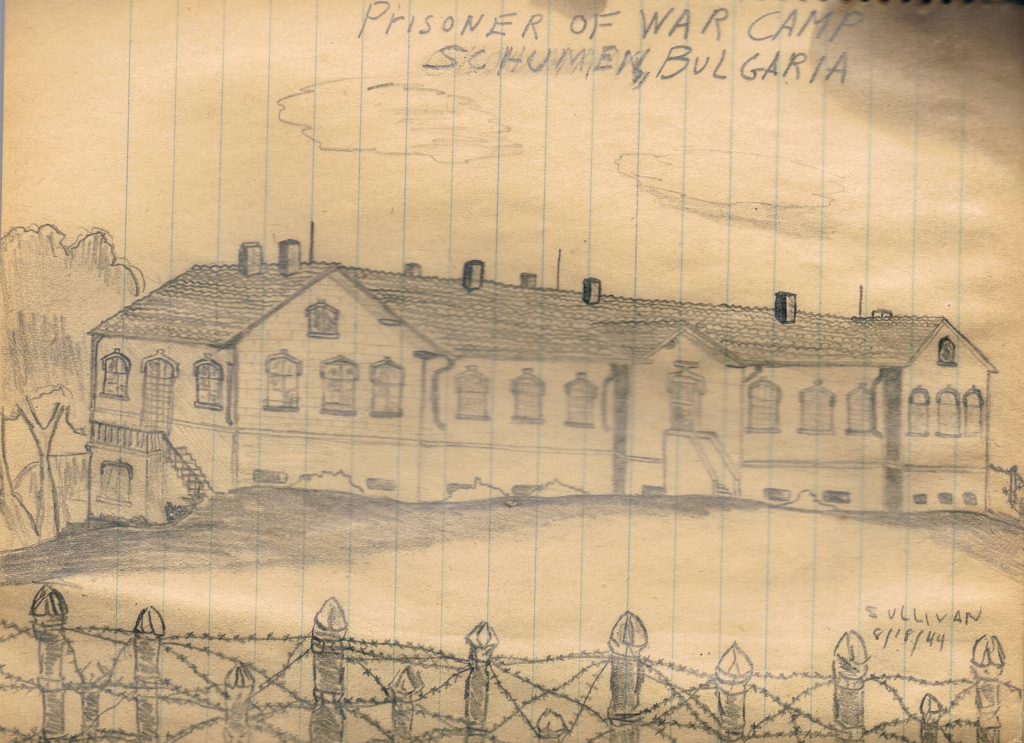

Mike enlisted in the Army when World War II started, earned a sharpshooter rating during sniper training, before becoming a tail gunner in a B-17 Flying Fortress. His plane, the Opissonya, was mortally wounded during Operation Tidal Wave, a raid on the Ploesti oil fields in Romania. Mike was badly wounded and his parachute was riddled with bullet holes. The bombardier, David Kingsley, strapped Mike in his own parachute, tossed him out the door and went down with the ship. He was captured and sent to a Bulgarian prison camp, returning home with memories and secrets he would only share with fellow veterans. When his wife pressed him for details many years later, he would say, “Honey, you don’t want to know. It’s not something I want to remember.”

After the war Mike returned to Chicago and moved back to his parents’ house. A budding artist, he enrolled at the Art Institute of Chicago and then landed a job as a graphic artist. On Saturdays, he and his buddies would go to one of the many dance halls around Chicago for a night of revelry. Sometimes they would crash Italian wedding receptions because there was always great Italian beef and no shortage of gorgeous young women who loved to dance. The revelry would often last until the wee hours of Sunday morning, when they attended the sunrise. Mass before hitting the sack. He was a confirmed bachelor with absolutely no interest in settling down and raising kids. Or so he believed.

Gloria was born on the South Side of Chicago 1933, to Joseph and Nadezda Shiplov, the last of eight children. They emigrated to the United States from “the old country,” although which “old country” was always a mystery. They might have come from Yellow Russia (now Belarus), or maybe Russia proper before it became the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Family members were always evasive about their history and any information pried from reluctant lips was suspect. There’s an old picture of Grandpa Joseph in a Cossack uniform, prompting speculation he may have fled the Bolsheviks. He arrived at Ellis Island with, according to his travel papers, a woman who was NOT Nadezda and whose fate remains unknown.

The only person who knew everyone’s secrets was old Muzyka, the undertaker for the Eastern European community, and he took those secrets to his grave. Peg says, “The Shiplov family crest should be engraved with “??? ???? – Everyone lies!”

Nadezda died when Gloria was two years old, and Joseph was ill-equipped to care for a tosed around among the siblings’ families until her sister Ann, twenty years her senior, and her husband John took Gloria in and raised her as their own.

Gloria graduated from Jones Commercial High School, a prestigious and rigorous institution that provided students a well-rounded education with business and personal training highly sought by employers. She learned secretarial skills and bookkeeping, but she dreamed of becoming a nurse. She was lucky enough to get a full scholarship to nursing school, on the condition that her family provide a small monthly sum for “incidentals.” Her father refused and never offered an explanation, so Gloria found a secretarial job at Teepak, a company that manufactured meat casings. Maybe his decision was rooted in Russian pride, or maybe he believed a woman should never aspire to be more than a housewife and mother. I’d like to think it was divine intervention, a little nudge in the direction of the inevitable.

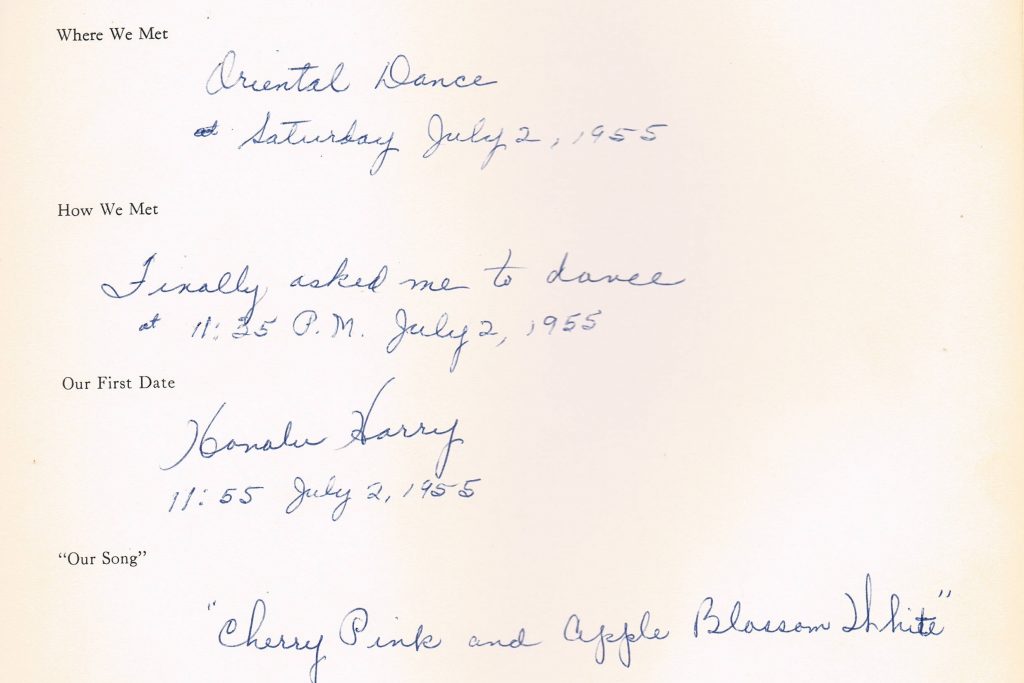

On Saturday nights Gloria and her pack of girlfriends made the rounds, dancing with eager young men at the dance halls or sometimes with soldiers at the local USO. One sultry summer evening in July she and her best friend, Marge, went to a “28-and-older” dance, even though Gloria was only 22 at the time. Mike Sullivan was also at that dance, and at the time had been dating three or four women, including one who assumed they were engaged, although no such proposal had ever been offered. He was still footloose and fancy free, committed to remaining single.

That changed at 11:35pm.

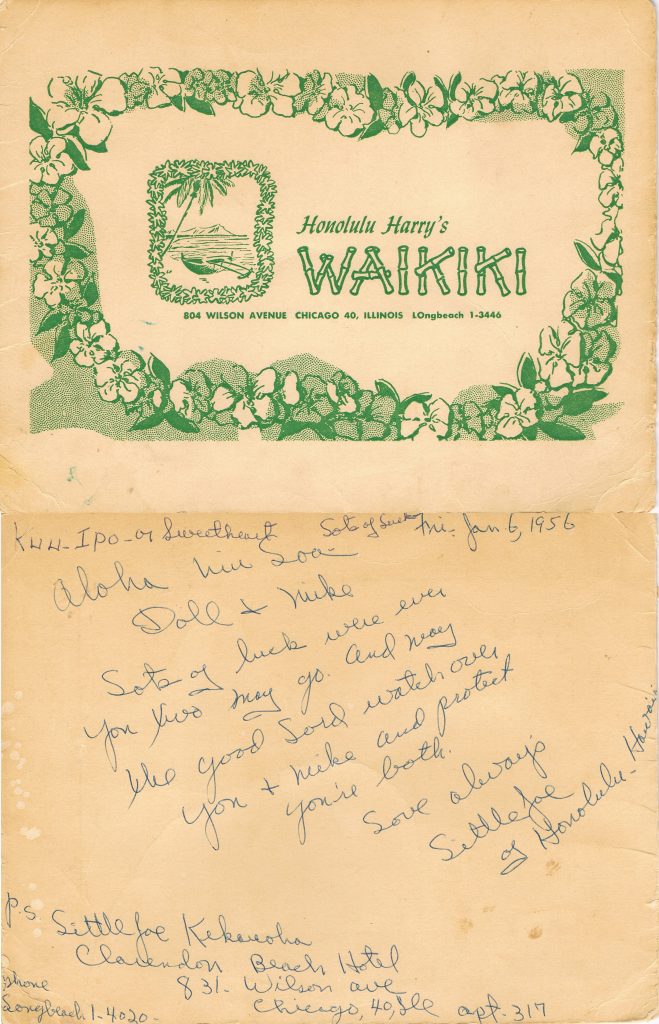

Gloria may have noticed him first because she later wrote “Finally asked me to dance at 11:35pm July 2, 1955” in her bridal keepsake book. Twenty minutes later they went to Honolulu Harry’s Waikiki for their first date. That was a much different time as few women today would leave with a man she’d only known for 20 minutes. But the heart knows what it wants. Later he would tell his daughters “I knew she was the one.”

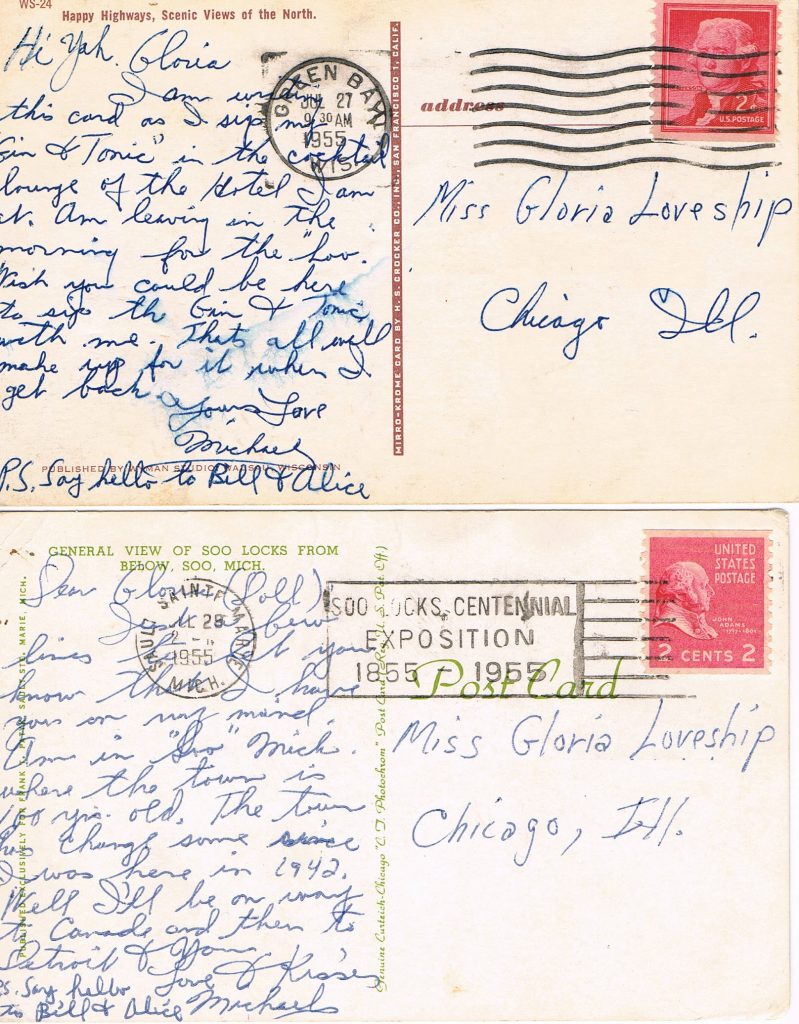

A few weeks later Mike was in Sault Ste Marie, Michigan, on his way to Canada and then Detroit to visit family. Never one to worry about minor details, he sent several postcards to Gloria “Loveship.” He lamented she was not with him in the hotel lounge to “sip the gin and tonic with me” and vowed to make up for the separation upon his return.

Gloria and Mike were inseparable. They celebrated Mike’s birthday at their favorite restaurant, Honolulu Harry’s that fall and her birthday a few months later.

New Year’s Eve 1955 was very special. They were gathered at the home of her sister and brother-in-law, Alice and Bill, to see in the New Year. At 7:40pm, Mike took Gloria’s hand into his, slipped a ring on her finger and said, “You’ll get the mate in six months.” When asked decades later why he didn’t formally say, “Gloria, will you marry me,” he replied, “There wasn’t any need because I knew she’d say ‘Yes!’.” In June 1956, she “got the mate.”

Mike, the formerly confirmed bachelor, settled down with the love of his life. They had two daughters and moved to the suburbs in 1964. He worked as a commercial artist at several companies in downtown Chicago until retiring in 1989. He turned down any promotions that would have meant less time with his family. He became notorious for “train-skunking” – scavenging the METRA commuter cars for newspapers and things left behind – a habit which once netted him a new bottle of scotch. Gloria was a stay at home mom until the girls were in middle school; then she worked as an office manager and bookkeeper until she retired.

They had a special ritual they followed every New Year’s Eve. Gloria would remove her rings that morning and Mike would hold on to them. Later that evening during whatever gathering they attended, Mike would have a Manhattan and Gloria would have a martini. At 7:40pm, he would quietly take her hand, slip the rings back on her finger and ask her to marry him. It was a private moment upon which the family would never intrude. They did that for 47 years until Mike’s passing in 2003.

Sometimes there really is a “happily, ever after.”

© Can Stock Photo / FotoMaximum