Wednesday

Morning started at 6 a.m. with the Procession of Medications, a pill to prevent reflux, and my nurse noting my lipase level was down to 2,000. A tech took my temperature, blood pressure and pulse oximetry. The day shift nurse, Katrina, brought more meds around 7:30 a.m. which I took with the water I wasn’t supposed to be drinking.

“Uh, didn’t they tell you not to drink?” Nope, this is the first I’ve heard.

She also injected a dose of Lovenox®, an anticoagulant to prevent a deep vein thrombosis (DVT), because it had been ordered, not because I really needed it. I didn’t have the presence of mind to question it because I was tired but it seemed superfluous. My risk for a clot was low since I hadn’t had major surgery, I wasn’t bedridden, I don’t smoke and I’m not pregnant. Yeah, I’m old and fat but so what? (I refused it the next day, which is good because that little sucker was $119!)

An hour later a woman from Respiratory Therapy, who looked and talked like the commandant at a German women’s prison, appeared with one of the newer brand name steroid/long acting bronchodilator inhalers. Remember what I said about hospital meds costing a lot more? This one retails for about $450 and lasts 14 days; the hospital charged $570. My generic version, which lasts a month, is $40 with GoodRx®.

“I have an inhaler for you and I’m going to teach you how to use it. You pull back the cover and it’s very important that you hold it correctly with the vent side up. Then you take a deep breath and hold it.”

I pulled out my albuterol rescue inhaler. “I’m a physician. I’ve been using inhalers for a long time.”

She snapped at me. “You should NOT have your own inhaler! We are responsible for you and must know every medication you are taking! Another respiratory therapist would turn you in.”

Now she reminded me more of General Burkhalter from Hogan’s Heroes. Turn me in? What is this, Stalag 17? Are you going to send me to the Russian Front?

She watched while I inhaled like toking from a bong, then put it in a plastic bag which she placed on the shelf below the TV. “Someone will come back tomorrow for your next dose.” You think I’m so stupid that someone has to watch me?

No, it’s because the hospital can charge $424 to “administer” the medication and $323 to “demonstrate” how to use it! What the hell do people without insurance do with those kinds of charges?

The Parade of the Grey Coats began around 9 am. Doctors (usually men) in white coats often cause spikes in patients’ blood pressures, so now most wear either grey or blue lab coats to minimize the psychological trauma. Or maybe it’s because white coats are a bitch to keep clean. (I have a royal blue lab coat with a Grateful Dead patch on the pocket.)

The internal medicine hospitalist showed up first. Now, I’m not sure what a hospitalist does other than generating revenue and confusion while making it possible for office-based internists to never set foot in the hospital. I’m sure I’ll get a lot of shit for that but my sister-in-law’s experience with hospitalists, who are usually much younger than the seasoned staff physicians, was exasperating.

He asked me to recount the events that ended with my admission, the third request if you’re keeping count.

“How are you feeling?”

“Better than when I came in.”

“Well, your lipase levels have come down nicely to around 2,000 with the I.V. fluid flushing it out. Do you mind if I examine you?”

He poked my abdomen in a few places. “Does that hurt?”

“Not much but you’re not as rough as the ER doc last night. Do you know Dr. Nell?”

He chuckled, “Yes, I like her, but she can be a little, uh, enthusiastic.” That’s a polite way of putting it.

“Your lipase levels suggest you have pancreatitis. You’re not an alcoholic and you don’t smoke so it’s likely caused by gallstones. That pain you had may have been a stone passing, especially since it didn’t last too long and you’re feeling better. I’m going to order an ultrasound of your gallbladder. We might be able to send you home later today, but we’ll have to wait for the GI guy to see you.”

We interrupt this tale for a moment of education and enlightenment.

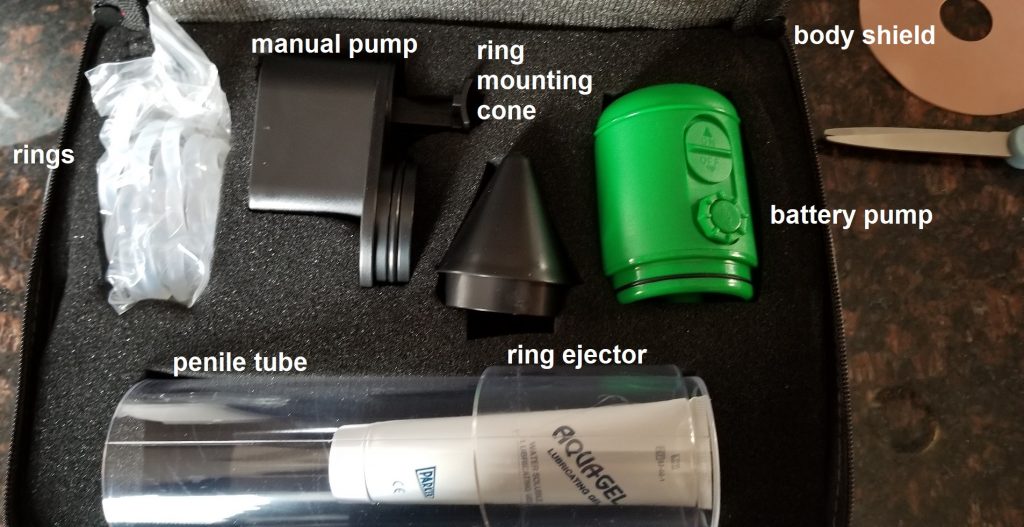

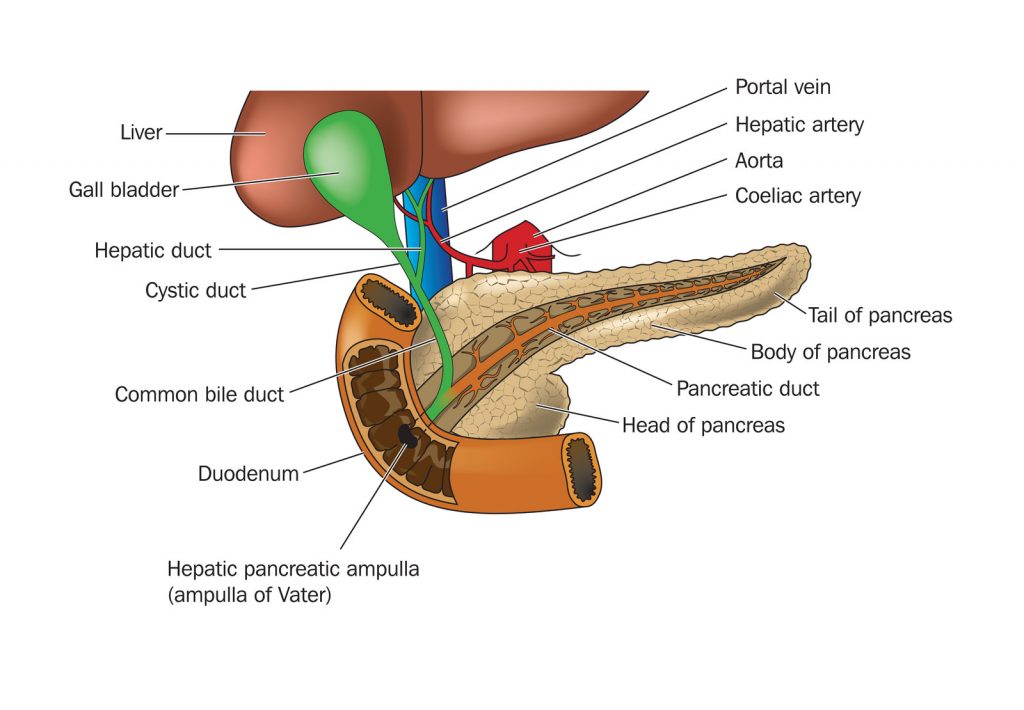

THE PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF BILIARY PANCREATITIS

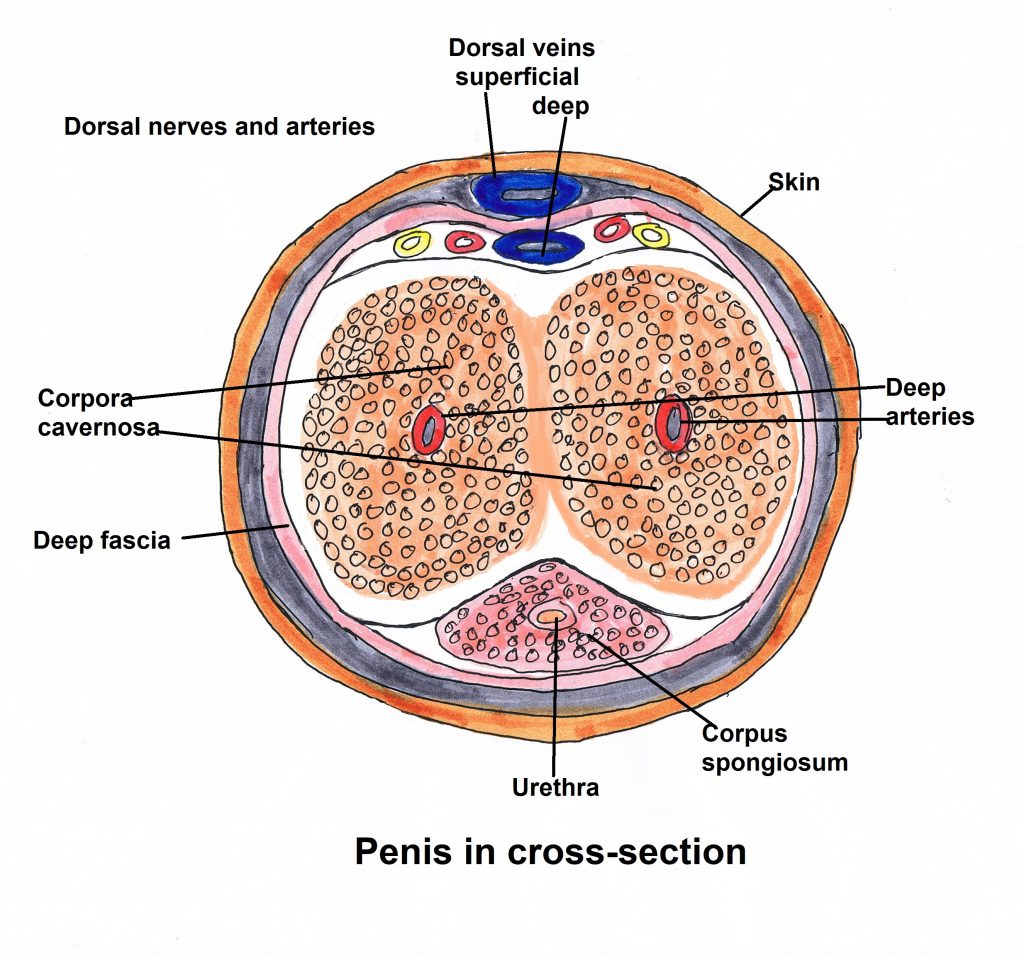

The gall bladder is a pear-shaped organ that lies below the liver. It stores and stores bile, which digests fats. Bile leaves the gall bladder through cystic duct. The pancreas also secretes digestive enzymes through the pancreatic duct which joins the cystic duct, forming the common duct. Both empty into the duodenum through the hepatopancreatic ampulla, also known as the Ampulla of Vater (Darth Vater?), which is controlled by the Sphincter of Oddi. Sounds like something out of Norse mythology.

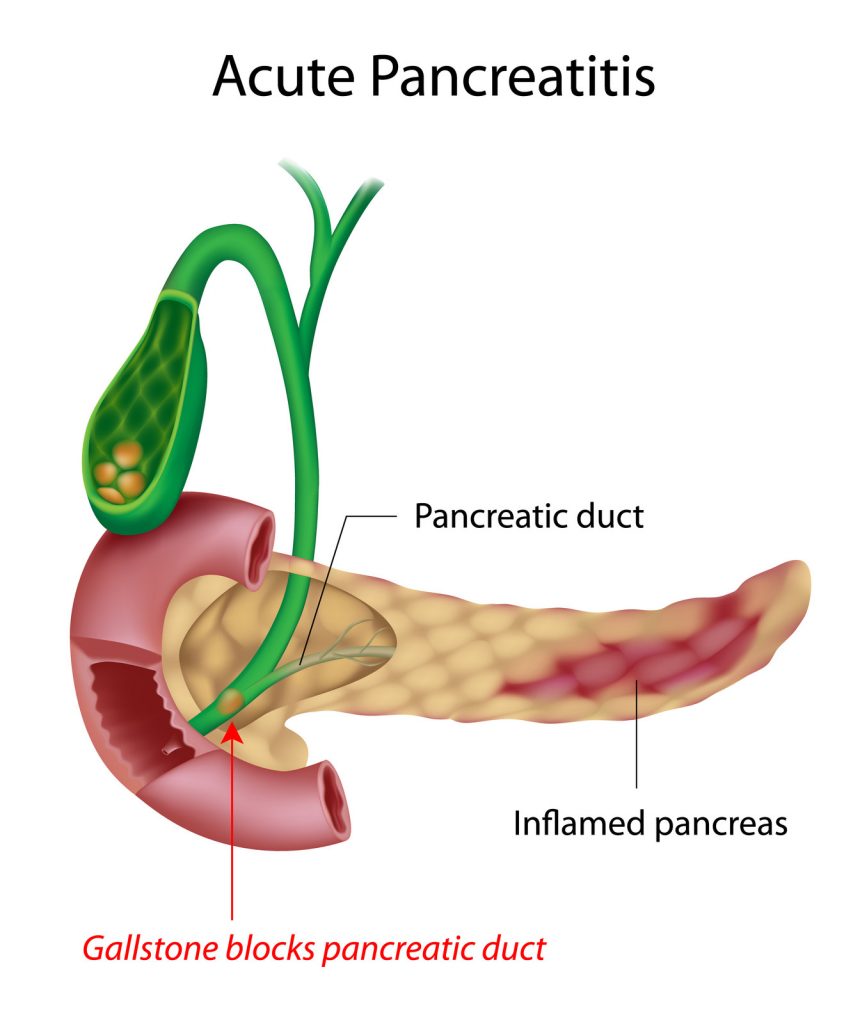

The gall bladder also provides a source of income for general surgeons when it becomes inflamed (cholecystitis), full of stones (cholelithiasis), or both. Stones form when, for unknown reasons, stuff in bile crystalizes and forms gallstones, in much the same way stuff in urine crystalizes to form kidney stones. If a stone gets stuck in the common duct, it blocks secretions from both the gallbladder and pancreas, resulting in gallstone pancreatitis, which is what I had. Pancreatitis can also result from excess alcohol consumption, smoking, prior abdominal surgery, obesity, infections, injuries, and pancreatic cancer.

Abdominal ultrasound is the easiest way of finding gallstones and often cholecystitis, as inflammation thickens the gallbladder wall. Other, and far more expensive, diagnostic methods include nuclear medicine scans, Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), or Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), looking directly into the duct with an endoscope.

A common home test for cholecystitis is consuming a greasy meal which results in excruciating upper abdominal pain; however, this is not medically recommended.

Now, back to the program already in progress

Peg arrived around 9:30am.

Did I ever mention Peg hates hospitals? No, she REALLY hates hospitals. Her mother said, “Hospitals are where you go to die.” If Peg has the big one at home, she wants me to just hold her hand and stroke her arm until she passes. Then, and only then, can I go through her office looking for the lam money.

She also thinks there is a lot of waste and abuse, albeit mostly inadvertently because no one thinks about cost in a hospital. This is largely true. I worked for a staff-model HMO thirty-five years ago. “Managed care” was withholding care from patients for profit and employed physicians weren’t good enough to work with “real doctors.” Forty years later most physicians are employed by heartless entities, and I got the last laugh.

“So, what’s happened so far? I talked to your nurse about 5:30 this morning and she said you had a good night.”

“Yeah, my lipase level has come down to two thousand something. I saw the hospitalist earlier; he thinks I have pancreatitis from passing a gallstone. He ordered an ultrasound and said I might get to go home…depending.”

“Do you have any pain?”

“No, I feel pretty good right now.”

Just then a guy from Patient Transportation appeared in the doorway. He took me down for ultrasound on my bed, reversing the previous night’s course. I stared at the ceiling again as we went left out of my room, into the elevator, down to the first floor, out and a couple of left turns before backing me into a cramped ultrasound exam room. The ultrasound tech introduced herself, squirted warm ultrasound gel on my abdomen and started the exam. About fifteen minutes later she finished.

“And….?”

“You’ve got gall stones, but you didn’t hear that from me.”

“My lips are sealed.”

As the transportation guy wheeled me out someone from nuclear medicine said: “We’re going to see you later.”

Once back in the room I told Peg what we’d both suspected. Then the gastroenterologist showed up – not exactly a fount of wisdom. At his request I repeated the events of the previous 12 hours for the third (or was it the fourth) time. He pushed on my abdomen, and I winced.

“Well, at least it’s in the right place. Your ultrasound showed you’ve got gallstones. We’re going to get a CT (Computed Tomography) scan to confirm the diagnosis and a general surgeon will see you later today.”

“Ok, how about not giving me another liter of fluid? I’ve had three in the past ten hours, and I’ve been peeing every two hours.”

“Yeah, that’s probably a good idea. We’ll also try you on clear liquids.”

Peg and had a discussion after he left.

“You told me it didn’t hurt, and you told him it did.”

“It didn’t hurt when you asked me. It hurt after he reefed on it because it’s inflamed, not because I’m lying to you.”

“Getting a CT scan to confirm what we already know is a waste of money! The ultrasound showed you have gallstones; a CT scan is redundant. It’s not going to give any better information. And THIS is why healthcare is so expensive!”

Peg had a point. If you’ve already made the diagnosis with a $1,000 ultrasound scan, why tack on another $3,000 for a CT scan to tell you the same thing? If an ultrasound might be difficult because of extreme obesity, then just do a CT. (Side note: Later that day the general surgeon told me the CT scan was used because ultrasound can’t evaluate the pancreas very well for things like fluid collections or tumors, which is important when considering surgery.)

We saw the cardiologist next and recited my history for the fifth time. I recognized his name; he is the “electrician” who did my sister-in-law’s cardiac ablation. She absolutely loves him, and his partner is my cardiologist, so I trusted whatever he had to say.

“Your EKG and troponin levels were normal. You haven’t had a recent stress test and we’ll have to clear you if you’re going to have surgery.”

I had a stress test in 2017 because I’ve no reliable family history and I was going to start work as a hospitalist. Unfortunately, a normal stress test doesn’t mean you won’t drop dead a few weeks later like Tim Russert.

There are two ways to do a stress test. The time-honored tradition is to hook a patient up to a 12-lead EKG, run him or her on a treadmill until the pulse is at least 130, and see what happens. ST segment changes suggest coronary artery blockage. (So does grabbing one’s chest and having the big one.) The test runs a few hundred bucks.

The other way is a cardiolite stress test, injecting the subject with a radioactive tracer and scanning the heart before and after the treadmill. A decrease in uptake after exercise suggests blockage and may indicate which artery/arteries are affected. The tracer and scan add several thousand bucks to the procedure, even though it is of questionable benefit in someone who has no history of coronary artery disease. Coronary angiography, injecting dye through the coronary arteries, is still the definitive test for detecting blockages.

The charge for an outpatient study is considerably less than doing the same thing in a hospital:

| Item | outpatient | inpatient |

|---|---|---|

| Treadmill | $325.00 | $1,200.00 |

| Tracer | $720.00 | $918.00 |

| Scan | $1,634.00 | $5,532.00 |

| Interpretation | $300.00 | $300.00 |

| TOTAL | $2,979.00 | $7,950.00 |

A nuclear med technician came in with a syringe containing the isotope in a shielded container and transportation took me down in a wheelchair instead of a gurney. This time I could at least see where I was going. The cardiac evaluation unit was below the first floor and reminiscent of the Batcave.

One of the women in the scanning room explained the procedure, then had me lay on the slightly uncomfortable scanner bed. The initial images took about six minutes, then they wheeled me across the hall to the treadmill room. Another tech applied twelve more EKG leads on my chest and abdomen, on top of the six leads I had for the portable monitor. The woman running the test explained what was about to happen.

“You’ll be on an incline on the treadmill. It will start out slowly for a few minutes, and then I’ll increase the speed until your heart rate gets to 130. You’ll have to keep that pace for at least a minute. Try to go as long as you can. When you need to stop, I’ll slow the treadmill for a one-minute cool down phase. I see you have exercise-induced asthma. Do you have an inhaler?”

“Yes, I do but the respiratory Nazi told me I shouldn’t have it in the hospital.”

“Well, she’s wrong; we like treadmill patients to have their inhalers on hand.”

Left hand, have you met right hand?

The incline was fairly steep, more than I’ve ever tried at home. I held onto the bar across the front of the treadmill to keep from falling backwards. The pace was manageable despite feeling I was hiking up a mountain.

Then, to quote Emeril Lagasse, she “kicked it up a notch.” Actually, several notches. It didn’t take long for me to hit the target heart rate. I managed two minutes at that speed before I told her I had to stop.

“Are you having any pain or trouble breathing?”

“No, I’m just way out of shape and too old for this shit.”

I went back into the scanner for about three minutes before being wheeled back upstairs. I napped for a while, while Peg sat in the corner playing with her Kindle and looking at the news feed on her phone. I figured no news was good news.

The day nurse came in a little after 1pm to tell me the CT scan was scheduled for around 4pm and I’ll get oral contrast to drink around 3pm. The guy from transportation arrived a little before 4, followed by the nurse.

“Wasn’t I supposed to drink some contrast?”

“Uh, you didn’t get it?” Would I be asking you if I had?

She sputtered a bit and disappeared, possibly to give someone an ass-chewing, and to get the CT scan rescheduled. Peg rolled her eyes.

“If you were just a regular patient, you would have gone for your scan without asking any questions. They would have done the CT, discovered you didn’t have the oral contrast, and sent you back upstairs, and repeated it later. And you wonder why I hate hospitals.”

I saw the surgeon around 6:30, after Peg had gone home to feed Baxter. We hit it off immediately. He extolled the virtues of removing gallbladders with a laparoscope and I told him about assisting on an open cholecystectomy when I was an intern. Back then they made an autopsy incision from the breastbone along the right rib margin, then pried the muscles apart to get to the gallbladder. The guy I helped with was fat and needed a very large retractor called a Joe’s Hoe for exposure. Yeah, it looked like one could till soil with it.

“There are two options. The first is to have the surgery since you are already in the hospital, and you’ve gotten cardiac clearance. The other option is letting you go home and scheduling this as an outpatient. I’d recommend doing it now because we know you have gallstones and you’re likely to have another attack within three months. It’s better to take care of it now, because I’ve seen people wait and then come in with a necrotic gallbladder. They end up in ICU on I.V. antibiotics and sometimes a ventilator because they are really sick.”

“My wife works long hours. I need to talk to her and make arrangements. What is the chance of passing another stone in the next two weeks?”

“It’s likely pretty low but not zero. You might want to just get it over with.”

Well, that sounded good to me; I wouldn’t have a lot of time to think about going under again. We talked about my prostatectomy; he said taking out my gallbladder wouldn’t take as long, and I could probably go home a few hours later.

“I know your surgeon. We’re actually very good friends, even if he did go to Ohio State.”

Oh God, he’s a Wolverine. They can be sooo insufferable! But he seems like a decent guy.

“In the meantime, you can have a clear liquid diet tonight. Don’t have anything after midnight in case you decide on surgery. I have one case in the afternoon.”

I called Peg.

“He said we can do it now or do it later. I told him you had to work and could we do it in a couple of weeks. He said we could but there was a chance of another attack before surgery.”

“Well, what do you want to do?”

“He’s coming back in the morning and you’ll probably be here before him, so you can ask him any questions. If I do it tomorrow, I won’t have a lot of time to think about it.”

“I’ll go along with whatever you want.”

Katarina brought me two cups of contrast just before 7pm.

“Drink these now and I promise you’ll be downstairs for your CT scan around 8pm.” Well, this better happen!

Someone arrived just before 8pm and took me down to the CT room. It was cold, probably to protect the equipment which can become very warm. The tech who met me was a scruffy guy who reminded me of the dude that drove the school bus down to the water when a bunch of us went canoeing at Turkey Run State Park in Indiana during college. (His “mandatory safety instructions” were “If the brakes go out on this bus, put your head between your legs and kiss your ass goodbye!”)

“Marian will help you lay on this skinny bed while I get everything set up. I’ll let you know when I push the I.V. contrast because your head will start to feel warm and then you’ll think you’ve peed your pants. You’ll have to hold your breath a few times but that doesn’t last long. Do you have any questions?”

“Nope, let’s just get this done.”

The scan was as he described. I held my breath a few times while the scanner did its thing. The I.V. contrast created a brief sensation of warmth in my head and nether regions, passing quickly. I was back upstairs by 8:30 and I called home to say goodnight to Peg and to Baxter, who wasn’t taking this very well at all. He paced Tuesday night until 2am and this promised to be another fitful night.

Maybe tomorrow would bring a reprieve from all this fun and excitement.

JOIN US NEXT TIME FOR THE SERIES FINALE!

Illustration Credits: All © Can Stock Photo

Pancreas: Blambs

Pancreatitis: alila

Pear: yayayoyo

Burger and Liver: FabioBerti