Every day I get in the queue

To get on the bus that takes me to you*

I heard the school bus stop at the corner outside our house as it does every weekday morning. Tomorrow will be the last time for the next three months; then the cycle starts over in August.

It made me think about going to elementary school in Bisbee, Arizona, back in the early 1960s. My school was built in 1955, during the Eisenhower years when the country built schools, hospitals and the Interstate Highway System, named for the last Republican president who thought government should serve the common folk. It was two stories, facing opposite directions and, since we were in the desert, all the classrooms opened to outside play areas. Snow was fascinating and rare. Valentine’s Day was always sunny and short-sleeve shirt weather. I’d never heard of winter coats and thermal underwear until we moved to Illinois.

We had brand new desks made of beige powder-coated steel with blonde wooden seats and a desktop. The walls were cream colored, and ceilings were covered with that white interlocking acoustic tile. The fluorescent lights looked like the old aluminum ice cube trays. There were simple wall clocks in every class and the principle’s office. I think they were square with a light gray face and a sweep second hand.

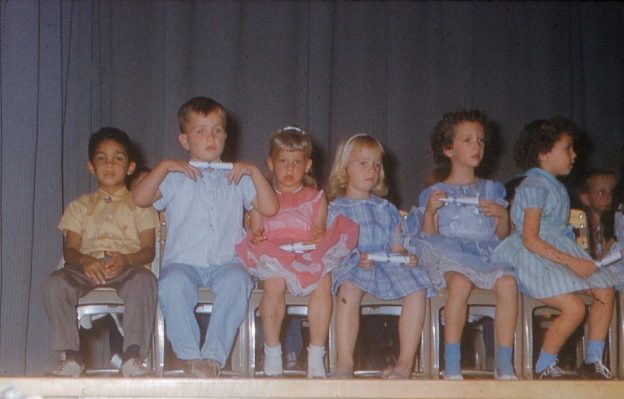

Some kids never liked school but for me it was a wonderful time. New pencils, maybe new school clothes, and new shoes because my feet were growing quickly. My first-grade teacher was suitably impressed when I spelled September for her. S-E-P… T-E-M… B-E-R. It was my birth month so why shouldn’t I know how to spell it. I was really excited when they picked me to be one of the three Wise Men in the Christmas play. I later figured out it wasn’t for my budding talent (I didn’t have any at 8 years old), but because I looked black.

Within a decade I would go from a relatively happy kid (despite the terror of living with an abusive alcoholic) to a sullen, angry teenager in the era of sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll. Half a century later I’m now a sullen, angry old man taking peculiar delight in telling solicitors to get the fuck off my porch, while imagining that inevitable eternal summer vacation.

*Lyrics from “Magic Bus” by Pete Townshend. (C) 1968, Fabulous Music, Ltd., London, England.