Christmas was pretty good when I was young. I hadn’t become acutely aware of being one of the “have-nots” and Christmas was a time when the perpetual underlying tension between my mother and stepfather seemed to fade for a few weeks. I looked forward to the respite, however brief it might be.

One of my memories is of the year we had our own Charlie Brown Christmas tree.

Almost everyone bought real trees back then, usually from a fenced-in lot that looked more like a hastily-erected corral. (The only artificial tree was an aluminum one that came with a rotating color wheel. Yuppie hipsters will pay big bucks for something most of us considered butt-ugly and crass.) We’d look around for a five footer that wasn’t dried out and hadn’t started shedding needles. Ten buck or so later, we’d stuff it into the trunk, take it home, and wrestle it into the tree stand, trying to make it look straight and steady enough so it wouldn’t tip over.

Most Christmas light strings were made of thick, tan wires attached to black plastic sockets outfitted with clips that attached to tree branches. Inside lights used the night light-sized C7 colored screw-in bulbs; outside strings had the larger C9 bulbs that were sometimes textured to imitate a flame. We used one white bulb to light up the Star of Bethlehem cutout in the front of my mothers’ old wooden Nativity stable. I never remembered the difference between “series” and “parallel” wiring, only that if a bulb went out on one type, you’d spend hours trying to track down the offender.

Some people lit their trees with the Noma bubble lights. Shaped like candles topping a street-light shaped reservoir filled with fluid, they bubbled when the bulbs heated up, providing hours of entertainment.

We had a couple of Shiny Brite ornament boxes filled with the solid color balls, since most of the original glass decorations had bit the dust in years past. There was always a wad of tangled-up hooks somewhere in the bottom and inevitably one or more hangers would pop out of the ball, daring me to put it back in without crushing the ball.

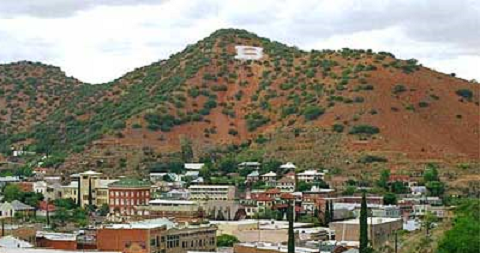

We never had much money and this year must have been especially tight. My stepfather decided we’d cut our own. That isn’t easy when you live in desert mountains and the dominant species are piñon and scrub oak, but hope springs eternal.

We drove out of town through the new tunnel and backtracked on Old Divide Road, which used to be the only access from the west, to Juniper Flats Road, which led to a plateau high above Route 80. Calling it a road is being charitable. It was a one-lane dirt trail of boulders and gigantic ruts on a 30-degree incline that would bust an axle if one was cavalier.

So we gingerly climbed about a mile until the road plateaued and we could breathe again. It was early evening and the sun was just about to set. We wandered around among the scrub until we came upon something that resembled an evergreen. It was small but I imagined lights and ornaments would make it suffice. My stepfather got out a carpenter’s half-hatchet, whacked the base a few times and we had our tree.

It was a lot smaller when we got home. The tree stand was far too big, so we put it in an old paint can filled with dirt. It looked a lot like Charlie Brown’s forlorn little tree. We dressed it up with one string of lights, a few ornaments and icicles and put a towel around the can for a tree skirt. Mom plugged in the lights and we stepped back.

As Linus would say three years hence, “It’s not a bad little tree. It just needs some love.”

And love made all the difference.