In December 2019 I had surgery for prostate cancer after my annual PSA levels, which I’d beengetting since 2007, started to gradually increase in 2017. The surgical pathology report showed my tumor was more aggressive than the biopsies, and even though the resection margins were clear, the tumor had already started to extend beyond the prostate. Radiation treatment for a recurrence sometime in my future was likely inevitable. I would get PSA tests every three months for a couple of years, then every six months if they remained negative or stable. Eventually, if all was well, I’d get annual PSA testing for the rest of my life.

My PSA levels during 2020 were <0.014 ng/ml, below the level the test can detect. The first one of 2021 was 0.015 ng/ml, a very insignificant increase. My levels rose again slightly before hitting a plateau between 0.022 – 0.027ng/ml. In December 2021 Dr. Fine, my surgeon, recommended I get tested every six months. In June 2022 the result was 0.023 ng/ml, and I was relieved it had gone down.

Six months later my PSA was 0.044 ng/ml, almost double the previous level.

I sat at my desk for several minutes, starting at the results on the monitor. Intellectually I’d known this was a possibility, but now it had become reality and I wasn’t sure how I felt. It wasn’t a death sentence and the low level meant I didn’t have a large cancer with metastases. I was more worried about how Peg would react.

“My PSA was point-zero four-four.”

“Ok. How do you feel about that? It’s been a good three years.”

“I dunno. I’m not surprised but I’m not sure what to do next. I should probably ask Dr. Fine what he thinks.”

“Well, I’ll support whatever you want to do.”

Now, back in the good (or bad) old days, before e-mail, smartphones, and websites, I called patients on an antique, corded landline to discuss important issues, like abnormal Pap smears and biopsy results. Now most large health care organizations use MyChart, an application that allows patients to schedule their own appointments, communicate with their healthcare providers, view their medical records and test results and pay outstanding bills, all while adding another degree of separation between patients and said providers.

My health care organization, Suburban Medical Center, is more interested in efficiency and revenue than customer service; their medical providers are tightly scheduled and controlled. They prefer to communicate via email, often after hours or during a rare break. There are no direct phone numbers to any of the offices; one has to call the generic department number. If I want to talk with a physician’s nurse, the department personnel might try to contact her (usually her).

I sent a message to Dr. Fine through MyChart.

Me: Level has doubled. Now what?

Dr. Fine: Since lower than 0.05, I recommend repeat PSA in 3 months. We can follow it a bit closer. If it continues to rise, we would consider planning for salvage pelvic radiation therapy.

Me: Pelvic salvage sounds like a sunken ship. So is this likely tumor cells, residual tissue or Karma messing with me?

Dr. Fine: Not Karma Salvage RT sounds bad but can provide cure for you. We went 3 years with just surgery which is great for your very aggressive cancer. If you’d like, I can arrange a visit with our radiation oncologist, Dr. Howard.

Me: Only if you think we’re at that point. It seems the experts don’t agree on the threshold; 0.05, 0.1 and 0.2 are the numbers I’ve come across.

Whether to treat or continue monitoring depends on the level and the rate of PSA increase, but in the end it’s what the patient wants to do. Ultimately, I decided that continuing to follow PSA levels would only increase my level of anxiety and delay the inevitable.

I asked the office to set up a referral and ran into my first problem. Someone entered a referral to Hematology/Oncology. I tried the “Find a New Provider” option in the application, but Radiation Oncology didn’t appear on the list. I found Dr. Howard on the organization’s general website but there was no option for making an appointment. Round and round we go.

I thought making an appointment in person would be more expedient, given the office is only a few miles from my house. Carla, a diminutive, cheerful woman greeted me as I walked in.

“My name is Carla. How can I help you?”

“Is this Dr. Howard’s office?”

“Yes, it is.”

“I had surgery for prostate cancer 3 years ago and now my PSA levels are going back up. Dr. Fine suggested I talk with Dr. Howard about radiation. I’ve been trying to make an appointment and it hasn’t been easy.”

“How soon are you hoping to see him?”

“Sometime in January is fine.” (I didn’t want to ruin Christmas with potentially bad news).

“Well, let me see what I can find.” She looked at the schedule for a few minutes.

“He’s got an opening on Tuesday January 10. You’ll meet with his nurse at 8:30am and she will go over a lot of information, then you’ll see Dr. Howard at 9:00am.”

I knew Peg would want to come to the appointments because she cares deeply about my wellbeing and doesn’t trust the health care system as far as she could throw it. She also asks far more questions than I do. I mostly wanted to talk about whether radiation was a good idea, how long it would last and what side effects to expect.

There were several other people in the waiting room on our appointment day. Everyone had to wear masks, but for some people rules are mere suggestions. There was an old guy in a wheelchair whose daughter hovered over him while he took sips of coffee in between hawking up hairballs, sans mask. Why have a coffee machine in the waiting room if you’re supposed to keep your face covered.

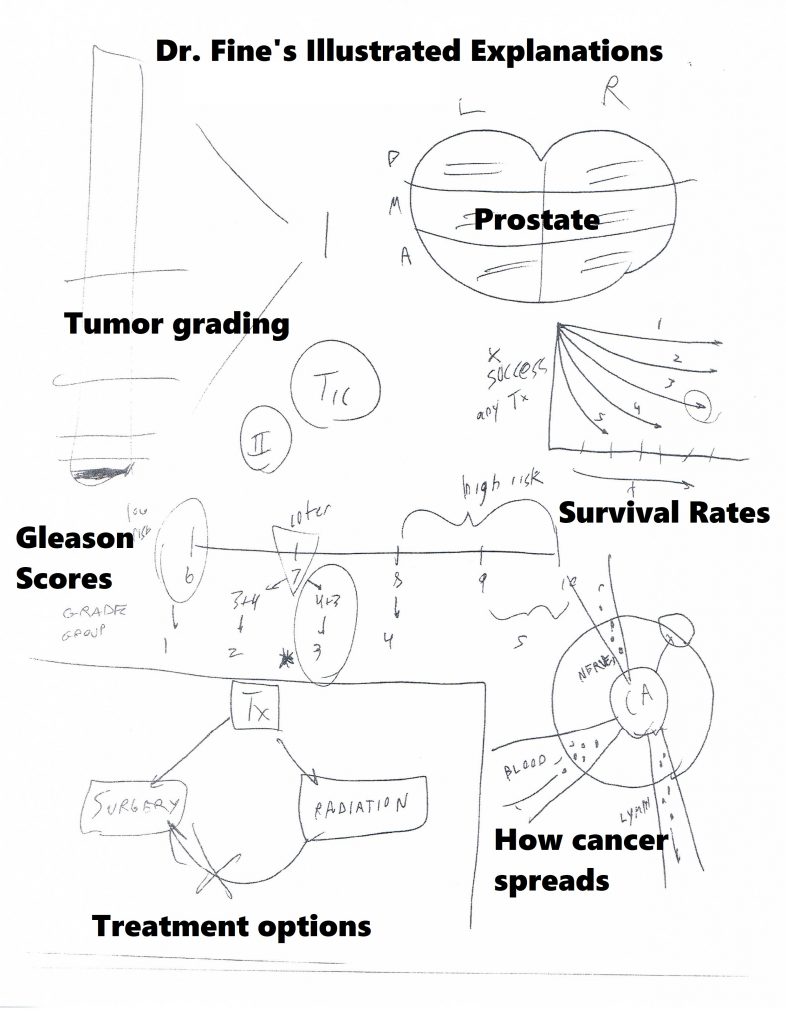

Danielle, the nurse who does pre-consult counselling, called us into a room and, over the next 25 minutes or so, gave us an overview of radiation treatments, side effects and how to deal with them, and warning signs like rectal or urinary bleeding. I don’t remember a lot of details; you’d probably have to ask Peg. Having the nurse see the patient first is probably a good idea, especially with elderly patients, given that nurses tend to be far more patient. She gave us a packet of information and left.

A few minutes later Dr. Howard came into the room and gave us a warm greeting. He was a tall, thin bald guy who reminded me of Ru Paul. I shamelessly told him I was a retired physician; that often changes the tenor of the interaction. There’s no need to dance around delicate subjects like clinical judgement, diagnostic or therapeutic uncertainties, disability or death.

“We’re here because my PSAs have gone up relatively quickly in the past six months. Given my tumor was more aggressive than the biopsies and there was extraprostatic extension, I figured we’d be doing this sooner or later. Is there an advantage to doing this now over waiting and following PSAs?”

“I know what I’d do in your situation. Radiation is like battling an army. I can fight against 1000 soldiers or 10,000 soldiers. So, doing it now increases the chance of cure.”

“So, how do you know where you’re shootin’?”

“We direct radiation at the bed where the prostate was. Before treatment we run what’s known as a CT simulation and map out the area. It takes about 2 weeks for the radiation physicist and me to set up a program. We’ll call you when we’re ready to start treatment. You’ll come in five days every week, but initially we’ll be putting you in to different time slots. You’ll have a regular time slot in a week or so as other patients finish their treatments.”

“How long is this likely to take?”

“Usually about 37-40 treatments. We’ll start doing PSAs again in about three to four months.”

I left with an appointment the following Tuesday at 4:00pm for the CT simulation.

Preauthorization

There’s a meme on the Internet that exquisitely illustrates the differences between the American and Canadian health care systems. (Since I don’t know if this is copyrighted, click here to view.)

Breaking Bad Canada

You have cancer.

Treatment starts next week.

END

Just because you have insurance doesn’t automatically mean the insurance company will approve payment without question. They require approval for anything that is likely to cost them a lot of money. Our insurer is very good at authorizing treatment. Other companies make their subscribers jump through a lot of hoops, even for cancer treatment, looking for ways to weasel out of paying. (A friend of ours whose wife ultimately died of her second cancer had to fight for things our insurer would have approved without question.)

Peg works for our insurance company, which stresses the employees are the “first line of defense against waste, fraud and abuse,” and as such are diligent guardians of precious health care dollars. And did I mention she hates the health care system in general?

She called our insurance company to ask about preauthorization for my simulation and treatment. This started a week-long exercise in futility, prompting her to wonder, “How do they manage to open the doors in the morning?”

“I started with one of our care coordinators who was very helpful. I asked about getting a pre-authorization for the CT simulation and therapy and how much this was likely to cost us out of pocket. She told me Suburban Medical hadn’t submitted pre-authorization requests yet, so she called Linda in Radiation Oncology. Ultimately, they determined there was no need for the pre-authorization for the simulation because it’s not for diagnosis. We’ll need it for treatment, but they can’t provide a cost estimate until after the provider submits a treatment plan.

“So, then I called someone else to try and get a ballpark figure for radiation treatments. He found general cost estimates for prostatectomy and brachytherapy but nothing for radiation. He suggested I call Suburban Medical, which I did but I left a voicemail and haven’t heard back.”

A week later she tried again.

“I called the care coordinator again; she hadn’t gotten a pre-auth yet, even though it’s been ten days since your consult and your simulation was at the beginning of this week. Suburban Medical told her she wouldn’t get any requests until the imaging results were available. It usually takes a couple of days to approve it, but she said she’d fast track it for us before treatment starts.

“I called Suburban Medical but whoever I spoke with couldn’t supply any cost estimates. She suggested I call our insurer back, which I did. Our rep said the provider should have this information easily available since this is their business. He’d need more information because estimates are based on the individual provider, the specific plan and reimbursement contract. He did say, ‘You’re likely to blow through your deductible and out of pocket before this is over.’

“I finally gave up and went to Google. Estimated costs for radiation therapy for prostate cancer recurrence range from $33,000 to $67,000.”

Wow!

I’m fortunate having insight into the health care system as well as a tenacious woman looking out for my interests. Imagine, though, the aggravation and anxiety a person with little disposable income has to endure, navigating through a confusing bureaucracy and wondering how to pay for several thousand dollars of treatment while coping with a cancer diagnosis.

I’ll discuss the simulation and treatment in my next post.

Featured image © Can Stock Photo / bertoszig