(I first wrote this 25 years ago. Perspective changes with time.)

I worked for a staff model HMO for nine years. Despite being a small cog in a sizeable organization, our Ob/Gyn department was like a second family to most of us. We knew about most of each other’s spouses (or ex-husbands). We shared our young kids’ accomplishments, antics and disappointments. We celebrated birthdays, expressed our condolences at the passing of elderly parents, and grieved together when a beloved young mother-to-be died in car crash. We had monthly department meetings at local restaurants after office hours, instead of trying to cram an agenda into a lunch hour.

Danni was the RN OB Intake Coordinator for our group. She was a gregarious soul with a kind heart and a good sense of humor. She spent an hour with each new mother-to-be at their first OB visit, talking about what to expect during pregnancy, what to do (eat healthy, wear a seatbelt and keep your appointments) what not to do (smoke, drink, anything blatantly stupid or dangerous). She was usually smiling, even when one of her appointments sorely tried her patience.

If she was having a particularly stressful day I would go to her office and wrap my arms around her. She said I gave great hugs; this was back when it wouldn’t trigger a visit from HR. I remember her colorful cable-knit sweaters under her lab coat and the warmth of her cheek against mine as she hugged me back, providing a brief respite from the day’s aggravations. Sort of like Mom telling you not to worry, that everything would be alright.

Danni suffered unrelenting physical pain from a tragic injury more than a decade earlier. We all knew about it, but to hear her talk it was more of an aggravation, something she’d learned to live with. Or maybe it was to deflect from the emotional torment she carried and of which only a few were aware.

I left the HMO in 1994; Corporate dissolved the staff model a few years later because “you cost us too much money.” Everyone found other jobs in town; Danni got a position with a local clinic. Our family had been torn asunder; we drifted apart and some connections withered from neglect.

I wandered for a couple of years, working in two different practices and a couple of locum tenens jobs before being hired to set up a practice in a small Southwestern town. I’d wanted to leave the long, gloomy Midwestern winters I’d endured for three decades and was trying to get out from under crushing but self-inflicted debt. (It hadn’t occurred to me that I was abandoning my kids as well, something I would later regret.)

In February, five months into the new practice, I flew Danni and Elizabeth, another former staff member, out to help train my nurse and receptionist. My new staff had no experience with an obstetrical practice, and I was used to someone else handling patient education. In retrospect, my support staff may not have been receptive to the intrusion but I needed the expertise.

Danni promised to send me forms and other information when she returned home. I called her several weeks later since I hadn’t received anything. She seemed distracted and vague but assured me she would “get around to it when I have time.” I should have suspected something was wrong. That was the last time I heard her voice.

One evening she sent her daughter to spend the night with the neighbor next door.

And ended her pain forever.

* * *

Linda, a nurse practitioner I worked with, called me early the next morning, sobbing.

“Danni is dead!”

“What happened?”

“I don’t know. She had her daughter Katie stay at her friend’s house last night. She found Dani when she came home to get ready for school. I don’t know why, but they found a note.”

She continued to cry.

“I remember she was suicidal when she left the clinic. I remember telling you she could never do that to Katy and you told me ‘Don’t bet on it.’ I don’t understand.”

“I do,” I replied. “I understand all too well.”

I talked with Peg later that day and told her what had happened.

“How are you handling all this?”

“As well as I can.”

“You know, I had a dream about you last week and I was afraid to tell you about it. You and I were talking and you told me you were going to kill yourself in the same tone you are using now. When I reminded you that you’d promised to keep going, you looked at me and said, ‘I was telling you what you wanted to hear.’ I heard the resignation in your voice. How could you do that?? Don’t you realize how much it would hurt everyone, including your kids???”

“Yeah, but I wouldn’t be around to know it.”

Over the next 2 days we talked about suicide; Peg was very angry.

“It’s so selfish! I don’t understand how she could calmly take her own life and leave her child with no one. There is always something else you can do.”

But for someone who has fallen into the abyss, such platitudes ring hollow. I know because I lived on the edge for almost 30 years and peered into the darkness many times. There comes a point when there is no more hope; when one has reached one’s limit of coping and can go no further. A point at which getting out of bed in the morning takes all the energy one has. There is nothing tangible to keep one moving, to make one want to take one more breath. Danni had reached her limit after years of constant physical pain and believing she had to go it alone. For all the people who cared and loved her, she finally could not continue.

The love of other people isn’t enough for some of us, because we don’t feel it is genuine or that we deserve it. On some level, I had long viewed that conditional “love” in the context of Billie Holiday’s song, God Bless the Child:

“Rich relations may give you

A crust of bread and such

You can help yourself

But don’t take too much.”

Ironically, Nietzsche said, “The thought of suicide is a great consolation: by means of it one gets through many a dark night.” I survived many of those dark nights and ultimately determined I didn’t want to jump into the void.

A couple of days later I got an e-mail from Liz.

“I got your message, thank you.

I feel numb. I can’t believe it. I will never understand.

Please, David, never do this!!!!!!”

* * *

Sarah was a 17-year old-gangbanger and troubled youth. Her father had also been a gang member, but he had turned his life around and tried to steer kids away from drugs, alcohol and living on the edge. Age and a stark reminder of mortality is often enough to trigger such an epiphany in adults, but teenagers either think they are immortal, or doomed to a life that can never change, so why bother.

Sarah was drunk the night she and some friends were playing chicken on the Interstate highway that ran north of town. They would lie on the white line while traffic approached at Autobahn speed, then run to the shoulder at the last moment. When Sarah’s turn came, she got up too late and was struck by a car. The local newspaper called it “an unfortunate accident” but some who knew her said she’d been severely depressed.

I went to the visitation with a family who had a troubled, angry 15-year-old daughter. I learned that when she threatened to run away from home, Sarah had talked her out it. “You don’t know how good you have it. You don’t ever want to live on the street!” Her friends and acquaintances, also “gangbangers,” appeared for the visitation, crying and holding on to each other for support.

I cried the tears I hadn’t been able to shed for Danni, and for those kids who felt they only had each other. I cried wondering why it took death to arouse family and friends from their oblivious slumber. Twenty-five years later I know some aren’t receptive to being helped, no matter how sincere the efforts.

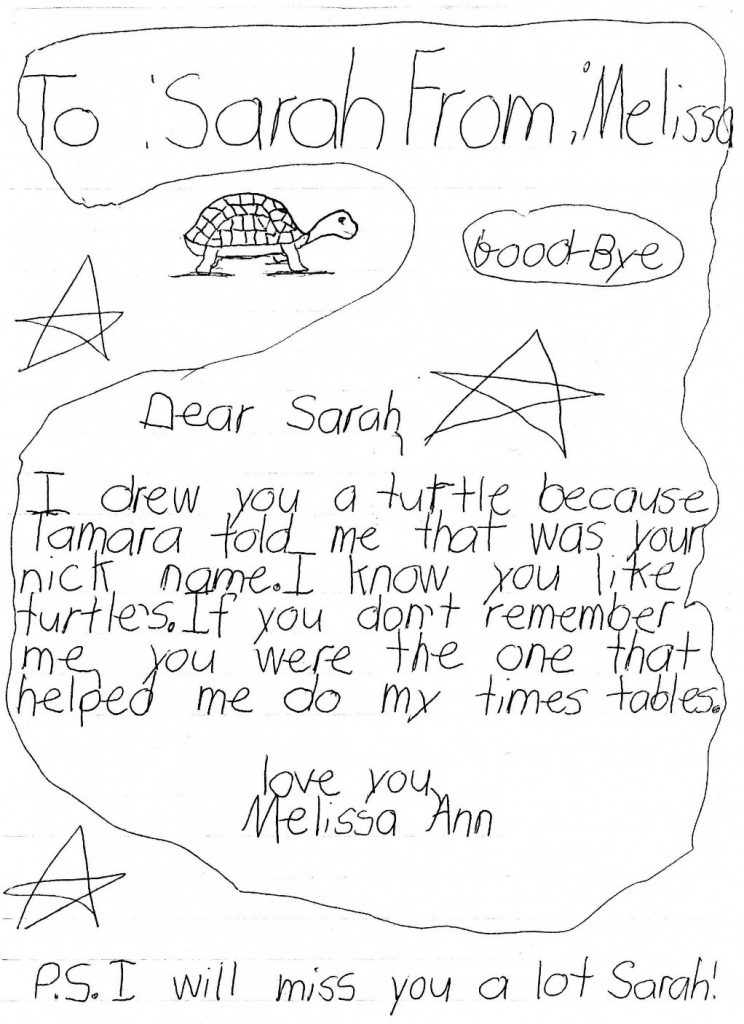

St. Mary’s Church was filled for the funeral. The gang members had printed T-shirts with “Turtle” (her nickname) over the left breast, and a memorial on the back: “In loving memory of Sarah Jo, 1980-1997.” During the eulogy Sarah’s cousin told the mourners, “If you love someone, tell them now. You never know when it will be too late.”

The procession to the cemetery stretched for 2 miles. After the priest finished, her friends released green and white balloons and sang for her. I couldn’t hear what they were singing. Instead, I heard a radio in the background playing “Forever Young” and then “That’s What Friends Are For.”

Melissa, 8 years old, wrote her own goodbye:

I held my 13 year old son and told him I loved him, even though I chewed his butt incessantly and tried to make him walk the straight and narrow. He blew it off, but deep inside I knew he understood and would always know that I loved him. I’d like to think my dad would have done the same.

A parent’s worst nightmare is having to bury a child long before his or her time.

A child’s worst nightmare is wondering what you did to make your parent commit suicide.

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 800-273-8255

Turtle © Can Stock Photo / shalamov