If anyone still wonders why health insurance is far more expensive than auto or homeowner’s insurance, here’s a simple explanation:

IF CAR INSURANCE WAS LIKE CONTEMPORARY HEALTH INSURANCE

- Employers would provide auto insurance as a benefit in lieu of higher wages

- Employers would either be self-insured or pay whatever rates they could negotiation with third party auto insurance companies, guaranteeing outrageous prices because “that is what the market will bear.”

- A run through the diagnostics and an oil change would be covered, but, like an annual exam and Pap smear, would be priced at $250. You could only have one oil change a year; if you needed more, you’d pay $250 out of pocket, unless you had the Federal Employees Auto Insurance Benefits, in which case you could have an oil change every week, subsidized by the taxpayers.

- Like dental coverage, your car would be eligible for professional detailing twice a year, at participating detailers.

- Like optical coverage, your car could get a new set of headlights and taillights every year, whether or not it needed them. Or, better yet, a new set of tires every year.

- Like pharmaceuticals, you’d have a $10 co-pay for a tank of regular gas, $20 for midrange gas and $35 for premium, but that tank would have to last a month. Your Auto Fuel Benefit Manager, however, would be arguing with the oil companies who would be charging $200, $500, or $5000*per tank to cover their “R&D” costs, which would be half of their marketing and advertising budget.

- If you were self-employed, unemployed, or lost your coverage because of “downsizing” or illness, you’d have to pay $250 for that oil change, a minimum $200/month for a tank of gas, or walk to work.

- If you were poor, you might qualify for Car-aid, but few gas stations or repair shops would accept your coverage and those that did would look down on you as a low-life draining the system, even though all you want to do is get to work and buy food without walking 16 miles in a blizzard, up hill, both ways.

- When you reached 62 or 65, you’d qualify for Car-care, which would cover repair and maintenance at the same rate, whether you owned an Escalade or a Prius. Your repair shop would be prohibited from providing any extra or discretionary work on your car, even if you could afford it, and be subject to fines and/or imprisonment.

- However, since you no longer had Auto Fuel coverage, you’d be back to paying $200 for a tank of gas, unless you had Car-care Gap Coverage, hawked by Mr. Bluewrench, dressed in knit coveralls, standing by the waiting room in a homey garage “for only $9.99 a month and you CAN’T be rejected.”

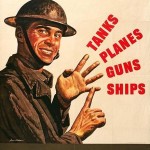

an said it was the first step towards Socialist America, warning “We are going to spend our sunset years telling our children and our children’s children, what it once was like in America when men were free.” We’d all be getting the same, substandard care from government-employed doctors in dreary Soviet-era clinics taking numbers and waiting months, if not years, for lifesaving care.

an said it was the first step towards Socialist America, warning “We are going to spend our sunset years telling our children and our children’s children, what it once was like in America when men were free.” We’d all be getting the same, substandard care from government-employed doctors in dreary Soviet-era clinics taking numbers and waiting months, if not years, for lifesaving care.